You are here: Urology Textbook > Bladder > Male stress urinary incontinence

Male Stress Urinary Incontinence: Diagnosis and Treatment

Definition of Stress Urinary Incontinence

The International Continence Society (ICS) defines urinary incontinence as "the complaint of any involuntary loss of urine". Stress urinary incontinence is urine leakage, which is associated with increased abdominal pressure and insufficient urethral sphincter mechanism. The main symptom of stress incontinence is the loss of urine on exertion, sneezing, or coughing.

Epidemiology of Male Urinary Incontinence

In older male patients (over 60 years), the prevalence of urinary incontinence is 7–10% (compared to 10–20% in older women). Only a minority, however, suffers from pure stress incontinence. Urge incontinence or mixed forms are much more frequent.

Causes of Male Urinary Stress Incontinence

Radical Prostatectomy:

The prevalence of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy is 0.5 to 87% in the literature. The high difference of the figures is due to different studies (by the surgeon or independent observer), different time intervals after surgery, and different definitions of urinary incontinence. In the long term, about 10% of patients require more than one pad per day due to urinary incontinence after prostatectomy. Risk factors for postoperative incontinence are advanced age, previous TURP, and advanced tumor stage.

There are several reasons for postoperative incontinence. Deep sutures of the pelvic floor cause direct damage to the external sphincter or its innervation in the case of bleeding or tumor infiltration. Postoperative hypermobility of the membranous urethra has been identified as another factor for sphincter weakness after radical prostatectomy. This finding has led to the development of suburethral slings [Gozzi, 2008], and modifications of the surgical technique were published [Rocco, 2009]. Occasionally, urge incontinence may develop after radical prostatectomy.

TURP and Prostatectomy for BPH:

Directly after the prostatic adenoma (TURP or simple prostatectomy) removal, the patient loses the prostatic component of the bladder closure mechanism. The urethral pressure profile resembles that of women. Postoperative detrusor overactivity is also a reason for urinary incontinence. An intact urinary sphincter may soon compensate for the increased workload with the help of behavioral therapy (adjusting drinking habits and micturition), physiotherapy, and anticholinergic medication [Hampel 2007].

Persisting urinary incontinence is rare after surgical treatment of BPH. Causes are de novo urge incontinence, stricture of the urethra or bladder neck, neurological disorders, iatrogenic sphincter injury, or already preoperative existing sphincter insufficiency. Iatrogenic sphincter injury is the cause for long-term urinary incontinence in 0.5% of patients after TURP [Rassweiler 2006].

Pelvic Fracture:

A pelvic fracture may lead to a distraction injury of the membranous urethra with stress urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

Other Causes:

Age, immobility, neurological diseases, subvesical obstruction and aging processes of the urinary tract can lead to urinary incontinence in men.

Signs and Symptoms of Male Stress Urinary Incontinence

According to the classification of Stamey, there are three grades of clinical SUI:

- Grade 1: loss of urine with a relevant increase in abdominal pressure, e.g., coughing, sneezing, or laughing.

- Grade 2: loss of urine with a lesser increase of abdominal pressure, e.g., walking or standing up.

- Grade 3: loss of urine unrelated to physical activity or position, e.g., standing or lying in bed.

Other symptoms: urge symptoms (frequency, nocturia), residual urine or urinary retention, weak urine flow, and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Diagnostic Workup of Male Stress Urinary Incontinence

History:

Ask for micturition symptoms, incontinence severity (pad usage), degree of bother, previous surgery, medications (e.g., alpha-blocker, clonidine), and neurological and urological diseases.

Urine analysis:

Urine sediment and urine culture to exclude a urinary tract infection.

Quantification of Stress Urinary Incontinence:

Documentation of drinking quantities, micturition volumes, incontinence episodes and pad changes with a micturition diary helps to quantify urinary incontinence. A time period of 24 to 48 hours is usually sufficient. For motivated patients with digital scales at home, the severity of the incontinence can be determined by weighing the incontinence pads each change.

Pad test for quantification of SUI:

An alternative to weighing the pads by the patient during the micturition protocol: a weighted pad is used after filling the bladder to 50% of its capacity. The patient should perform defined provocation exercises (stair climbing, jumping, coughing), and the pad should be weighed again. Urine loss of more than 25 g is considered severe urinary incontinence.

Urodynamics:

A urodynamic study is the best diagnostic tool to differentiate between urge incontinence, stress urinary incontinence, or mixed forms.

Cystoscopy:

Cystoscopy is important for the assessment of the residual sphincter function. Furthermore, cystoscopy identifies strictures of the urethra or bladder neck.

Conservative Treatment of Male Urinary Incontinence

Management of Urinary Incontinence:

Management of urinary incontinence with condom urinal or usage of absorbent pads. Some men may prefer the use of a suprapubic catheter.

Physiotherapy:

Physiotherapy with pelvic floor exercises aims at strengthening the sphincter muscle. The pelvic floor exercises may be more efficient with biofeedback. After radical prostatectomy, improvement in urinary incontinence may be expected up to one year after surgery. Randomized trials showed a significant effect of physiotherapy to achieve early continence, but its effect is only minor for long-term results [MacDonald 2007].

Drug Therapy:

Anticholinergic medication is effective in mixed urinary incontinence and urge incontinence. A specific drug therapy against stress urinary incontinence is possible with duloxetine, a serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Duloxetine is not approved for usage in men; it may be offered as an "off-label" treatment [Schlenker, 2006]. A therapeutic trial is only useful for mild stress incontinence; many contraindications must be respected.

Surgical Treatment of Male Stress Urinary Incontinence

Useful long-term results exist only for the artificial sphincter; all other treatment options are less invasive but still have to prove to be reliable in the long term.

Bulking agent injections:

Different materials can be injected to support the weakened sphincter in its closing function. Injections produce a submucosal cushion and provide limited efficiancy in mild urinary incontinence. Bulking agents like collagen have the disadvantage that it is absorbed, and the effect wears off. Nonabsorbable materials may lose their effect by dislocation. Autologous myoblasts and fibroblasts obtained good results in initial studies [Mitterberger 2008] [Strasser, 2007], but the results could not be reproduced, and the studies were challenged academically.

ProACT device:

The ProACT device consists of two small implantable balloons, which increase the pressure on the membranous urethra [Huebner 2007].

Non-adjustable male slings:

Bone anchored bulbourethral sling (InVance) [Guimaraes 2009], retrourethral sling without bone anchorage (Advance) [Gozzi 2008]. The prerequisite for successful therapy is (residual) sphincter activity, which can be supported mechanically.

|

Adjustable sling systems:

Argus system or Reemex system [Romano, 2006].

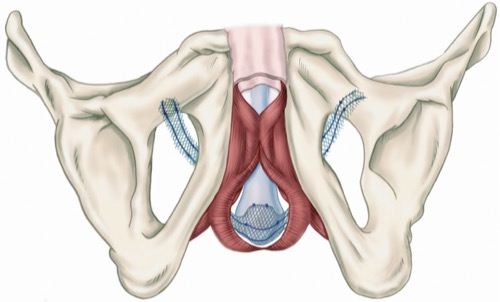

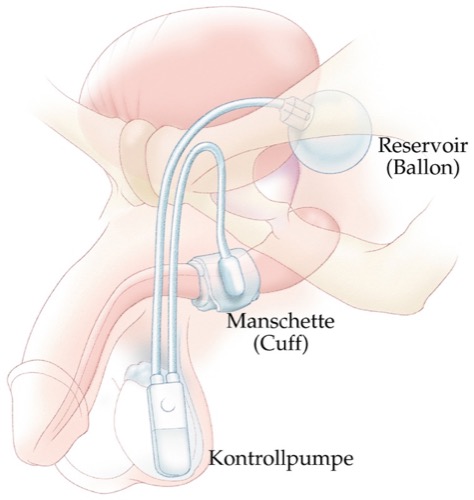

Artificial urinary sphincter:

The artificial urinary sphincter is the treatment of choice if there is a complete absence of sphincter function or after the failure of the above-mentioned treatment options, see fig. artificial sphincter AMS 800.

|

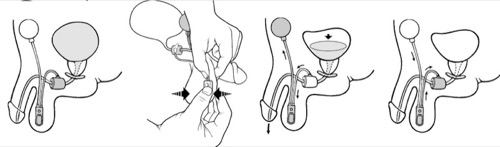

After surgery, the results regarding urinary continence are excellent. The disadvantages are the relatively high risk for surgical revisions (up to 50% within five years). Mechanical failure, cuff erosion of the urethra, and infections are the most common complications [Hussain 2005]. To operate the artificial sphincter, the patient should have a certain manual dexterity and intellectual insight [fig. control of the AMS 800 artificial urinary sphincter].

|

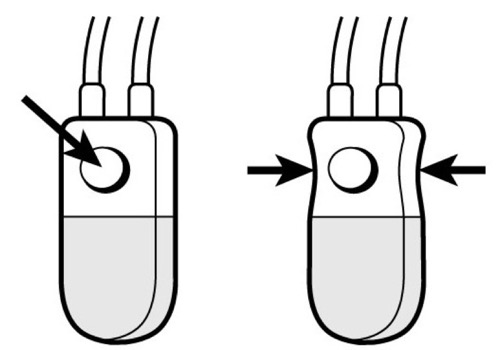

It is important to deactivate the artificial urinary sphincter before performing transurethral manipulations, see fig. deactivation of artificial urinary sphincter.

|

| SUI in women | Index | Overactive bladder |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Gozzi, C. u. a. (2008). [Functional retrourethral sling. A change of paradigm in the treatment of stress incontinence after radical prostatectomy]. In: Urologe A 47, S. 1224–1228.

Hampel, C. u. a. (2007). [Established treatment options for male stress urinary incontinence]. In: Urologe A 46, S. 244–8, 250–6.

Hussain, M. u. a. (2005). The current role of the artificial urinary sphincter for the treatment of urinary incontinence. In: J Urol 174, S. 418–424.

Hübner, W. A. und O. M. Schlarp (2007). Adjustable continence therapy (ProACT): evolution of the surgical technique and comparison of the original 50 patients with the most recent 50 patients at a single centre. In: Eur Urol 52, S. 680–686.

MacDonald, R. u. a. (2007). Pelvic floor muscle training to improve urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a systematic review of effectiveness. In: BJU Int 100, S. 76–81.

Mitterberger, M. u. a. (2008). Myoblast and fibroblast therapy for post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence: 1-year followup of 63 patients. In: J Urol 179, S. 226–231.

Rassweiler, Jens u. a. (2006). Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)–incidence, management, and prevention. In: Eur Urol 50, 969–79; discussion 980.

Romano, S. V. u. a. (2006). An adjustable male sling for treating urinary incontinence after prostatectomy: a phase III multicentre trial. In: BJU Int 97, S. 533–539.

Schlenker, B. u. a. (2006). Preliminary results on the off-label use of duloxetine for the treatment of stress incontinence after radical prostatectomy or cystectomy. In: Eur Urol 49, S. 1075–1078.

Strasser, H. u. a. (2007). Autologous myoblasts and fibroblasts versus collagen for treatment of stress urinary incontinence in women: a randomised controlled trial. In: Lancet 369, S. 2179–2186.

Deutsche Version: Belastungsinkontinenz des Mannes

Deutsche Version: Belastungsinkontinenz des Mannes

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.