You are here: Urology Textbook > Bladder > Bladder cancer

Bladder Cancer: Definition, Epidemiology, and Etiology

- Bladder carcinoma: Definition, Epidemiology and Etiology

- Bladder carcinoma: Pathology and TNM tumor stages

- Bladder carcinoma: Symptoms and Diagnosis

- Bladder carcinoma: Surgical Treatment

- Bladder carcinoma: Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy of Metastases

Definition

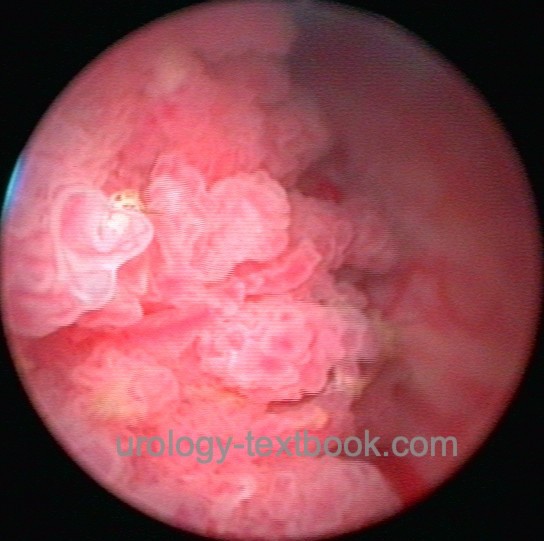

Bladder cancer is a malignant tumor that originates from the epithelial cells of the urinary bladder. Review Literature: EAU guidelines superficial bladder cancer. EAU guidelines of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer. German S3 guidelines bladder carcinoma Harnblasenkarzinom.

|

Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer

- The second most common tumor of the urogenital tract

- Lifetime prevalence (up to the age of 75 years) is 2-3% for men and 0.5-1% for women.

- Incidence in the European Union: 20 per 100,000 for men and 5 per 100,000 for women

- Mortality in the EU: 8 per 100,000 for men and 3 per 100,000 for women.

- Cancer statistics: incidence 5th position in men and 11th position in women. The incidence is increasing (30% in 15 years).

- Mean age at diagnosis: 65--75 years. Less than 1% of bladder cancers occur in patients less than 40 years.

- 70% have superficial bladder cancer at diagnosis, and 30% present with locally advanced tumor with infiltration of the tunica muscularis. 15% of patients are already metastasized.

- The mean age at death is 80--82 years.

Etiology and Pathogenesis of Bladder Cancer

Review literature: (Kalble, 2001) (Leppert et al., 2006) (Plná and Hemminki, 2001).

Smoking and Bladder Cancer:

Smoking increases the risk for bladder cancer three to fourfold. In Europe, about half of urothelial carcinomas in men and one-third in women are attributable to smoking. Smokers and ex-smokers more often experience tumor recurrence after superficial bladder treatment than non-smokers (Lammers et al., 2011). A dose-effect relationship is well established. The relative risk increases by 1 to 6 times, depending on the length of smoking and the number of cigarettes smoked. Quitting smoking avoids a further increase in the tumor risk (IARC, 2004).

Occupational Exposure:

Occupations with exposure to risk factors for bladder cancer are in the chemical industry processing paint, metal or petroleum products, steel industry, auto mechanics, leather industry, and dental technicians. Identified risk factors are azo dyes, benzidine, naphthylamine, toluidine, aminobiphenyl, aromatic amines, diesel exhaust, and carbon black. Urothelial carcinoma is a recognized occupational disease with sufficient exposure and a reasonable latency period. In Europe, up to 10% of bladder cancers are caused by occupational exposure. In developing countries figures of bladder carcinoma are rising due to increased occupational exposure without safety guidelines.

Influence of gender:

Although the risk of developing the disease is significantly higher for men, bladder carcinoma is in a higher tumor stage in women at the time of initial diagnosis; this corresponds to higher mortality after radical cystectomy (HR 1,2) (Liu et al., 2015). The higher tumor stage in women is partly explained by a different diagnostic approach in the case of hematuria; in women, the differential diagnosis urinary tract infection is more often accepted as the cause, and cystoscopy is not done (Cohn et al., 2014).

Fluid Intake and Bladder Cancer:

It is controversial whether an increased fluid intake leads to a reduction in the risk of bladder cancer. Individual studies have shown this connection. Coffee or alcohol are not risk factors for bladder cancer (Brinkman et al., 2008).

Nutrition and Bladder Cancer:

A healthy diet rich in fruits and vegetables (e.g., Mediterranean diet) lowers the risk of bladder cancer. The metabolic syndrome is an established risk factor for bladder carcinoma (Teleka et al., 2018). Sweeteners were suspected to be a risk factor for bladder cancer, but modern studies did not find any evidence (Brinkmann et al., 2008).

Aristololchic acid:

Aristololchic acid causes Balkan nephropathy (chronic interstitial nephritis, chronic kidney disease, and urothelial carcinoma). Aristololchic acid is found in the plant Aristolochia clematitis and consumed through contaminated flour; additional sources are Chinese herbal medicine (Grollman et al., 2007).

Drugs and Bladder Cancer Risk:

The following substances are recognized risk factors for bladder carcinoma: cyclophosphamide, Chinese herbs containing aristolochic acid, and antidiabetic pioglitazone. The causal relationship between phenacetin and other NSAIDs in causing bladder cancer remains contradictory.

Chronic Urinary Tract Infection and Bladder Cancer:

Chronic urinary tract infections over a long time are a risk factor for bladder cancer (e.g., patients with schistosomiasis, bladder stones, or long-term catheters). The risk is more pronounced for squamous cell carcinoma than for urothelial carcinoma (Abol-Enein et al., 2008).

Molecular Biology of Bladder Cancer:

The following genetic changes increase the risk of bladder cancer or correlate with tumor stage:

Activity of N-acetyltransferases (NAT1 and NAT2):

N-acetyltransferases are essential for the inactivation and elimination of nitrosamines. Slow enzyme activity of N-acetyltransferases carries a higher risk of developing bladder cancer, since environmental factors causing bladder cancer are slower inactivated. The epidemiological relationship is particular prominent in patients with a smoking history.

Lynch syndrome:

Lynch syndrome or hereditary non-polyposis-associated colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is an inherited form of colon cancer without the occurrence of many polyps in the colon. Mutations in DNA mismatch repair proteins also increase the risk of urothelial carcinoma.

Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes:

Increased expression of oncogenes like RAS or p21. Deletion or loss of action mutations of tumor suppressor genes like p53 or retinoblastoma gene RB1. The expression of PD-L1 correlates with the treatment response with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Chromosomal changes:

The loss of the long arm of chromosome 9 is detectable in all stages of bladder cancer. In advanced tumors, the loss of the short arm of chromosome 11 and 17 are additional findings.

Further molecular changes of bladder cancer:

FGF receptor mutations, increased expression of laminin receptors, increased secretion of type IV collagenase and autocrine motility factor, and increased expression of EGF receptors.

Molecular subclassification:

Modern laboratory methods (including next-generation sequencing) can simultaneously record numerous changes at protein, RNA, and DNA levels and allow a molecular subclassification of bladder carcinomas into luminal, basal-squamous, and neuronal subtypes (Robertson et al., 2017). The changes at the molecular level can enable a better selection of targeted therapies.

| Bladder cancer: | Index | Bladder cancer pathology |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Abol-Enein, H.

Infection: is it a cause of bladder

cancer?

Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl, 2008, 79-84.

Amin und Young 1997 AMIN, M. B. ; YOUNG, R. H.:

Primary carcinomas of the urethra.

In: Semin Diagn Pathol

14 (1997), Nr. 2, S. 147–60

Babjuk, M.; Burger, M.; Compérat, E.; Gonter, P.;

Mostafid, A.; Palou, J.; van Rhijn, B.; Rouprêt, M.; Shariata, S.;

Sylvester, R. & Zigeuner, R.

Non-muscle-invasive Bladder CancerEAU

Guidelines, 2020 https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer/

Brinkman, M. & Zeegers, M. P.

Nutrition, total

fluid and bladder cancer.

Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl, 2008,

25-36.

Cohn, J. A.; Vekhter, B.; Lyttle, C.; Steinberg,

G. D. & Large, M. C.

Sex disparities in diagnosis of bladder cancer

after initial presentation with hematuria: a nationwide claims-based

investigation.

Cancer, 2014, 120, 555-561

DGU; DKG; DKG & Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie S3-Leitlinie (Langfassung): Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie und Nachsorge des Harnblasenkarzinoms. https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/harnblasenkarzinom/

Helpap und Kollermann 2000 HELPAP, B. ;

KOLLERMANN, J.:

[Revisions in the WHO histological classification of urothelial

bladder tumors and flat urothelial lesions].

In: Pathologe

21 (2000), Nr. 3, S. 211–7

IARC (2004) Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 83. Tobacco Smoke and Involuntary Smoking. World Health Organization.

Kalble 2001 KALBLE, T.:

[Etiopathology, risk factors, environmental influences and

epidemiology of bladder cancer].

In: Urologe A

40 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 447–50

Kataja und Pavlidis 2005 KATAJA, V. V. ;

PAVLIDIS, N.:

ESMO Minimum Clinical Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and

follow-up of invasive bladder cancer.

In: Ann Oncol

16 Suppl 1 (2005), S. i43–4

Krieg und Hoffman 1999 KRIEG, R. ; HOFFMAN, R.:

Current management of unusual genitourinary cancers. Part 2: Urethral

cancer.

In: Oncology (Williston Park)

13 (1999), Nr. 11, S. 1511–7, 1520; discussion 1523–4

Lammers, R. J. M.; Witjes, W. P. J.; Hendricksen, K.;

Caris, C. T. M.; Janzing-Pastors, M. H. C. & Witjes, J. A.

Smoking

status is a risk factor for recurrence after transurethral resection of

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Eur Urol, 2011,

60, 713-720

Lampel und Thuroff 1998a LAMPEL, A. ;

THUROFF, J. W.:

[Bladder carcinoma 1: Radical cystectomy, neoadjuvant and adjuvant

therapy modalities].

In: Urologe A

37 (1998), Nr. 1, S. 93–101

Lampel und Thuroff 1998b LAMPEL, A. ;

THUROFF, J. W.:

[Bladder carcinoma. 2: Urinary diversion].

In: Urologe A

37 (1998), Nr. 2, S. W207–20

Leppert u.a. 2006 LEPPERT, J. T. ; SHVARTS,

O. ; KAWAOKA, K. ; LIEBERMAN, R. ; BELLDEGRUN,

A. S. ; PANTUCK, A. J.:

Prevention of bladder cancer: a review.

In: Eur Urol

49 (2006), Nr. 2, S. 226–34

Liu, S.; Yang, T.; Na, R.; Hu, M.; Zhang, L.; Fu,

Y.; Jiang, H. & Ding, Q.

The impact of female gender on bladder

cancer-specific death risk after radical cystectomy: a meta-analysis of

27,912 patients.

International urology and nephrology, 2015,

47, 951-958

Michaud u.a. 1999 MICHAUD, D. S. ; SPIEGELMAN,

D. ; CLINTON, S. K. ; RIMM, E. B. ; CURHAN,

G. C. ; WILLETT, W. C. ; GIOVANNUCCI, E. L.:

Fluid intake and the risk of bladder cancer in men.

In: N Engl J Med

340 (1999), Nr. 18, S. 1390–7

Plna und Hemminki 2001 PLNA, K. ; HEMMINKI, K.:

Familial bladder cancer in the National Swedish Family Cancer

Database.

In: J Urol

166 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 2129–33

Rajan u.a. 1993 RAJAN, N. ; TUCCI, P. ;

MALLOUH, C. ; CHOUDHURY, M.:

Carcinoma in female urethral diverticulum: case reports and review of

management.

In: J Urol

150 (1993), Nr. 6, S. 1911–4

Robert-Koch-Institut (2015) Krebs in Deutschland 2011/2012. www.krebsdaten.de

Stein u.a. 2001 STEIN, J. P. ; LIESKOVSKY,

G. ; COTE, R. ; GROSHEN, S. ; FENG, A. C. ;

BOYD, S. ; SKINNER, E. ; BOCHNER, B. ;

THANGATHURAI, D. ; MIKHAIL, M. ; RAGHAVAN, D. ;

SKINNER, D. G.:

Radical cystectomy in the treatment of invasive bladder cancer:

long-term results in 1054 patients.

In: J Clin Oncol

19 (2001), Nr. 3, S. 666–75

Weissbach 2001 WEISSBACH, L.:

[Palliation of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder].

In: Urologe A

40 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 475–9

Witjes, J.; Compérat, E.; Cowan, N.; Gakis, G.;

Hernánde, V.; Lebret, T.; Lorch, A.; van der Heijden, A. & Ribal, M.

Muscle-invasive

and Metastatic Bladder Cancer

EAU Guidelines, 2020 https://uroweb.org/guidelines/bladder-cancer-muscle-invasive-and-metastatic/

Deutsche Version: Harnblasenkarzinom

Deutsche Version: Harnblasenkarzinom

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.