You are here: Urology Textbook > Prostate > BPH > Diagnostik workup

Diagnosis of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: definitions, epidemiology and etiology

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: signs and symptoms

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: diagnosis

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: medical treatment

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: surgical treatment

Review literature: (Burnett und Wein, 2006) (DGU guideline) (EAU guideline: Non-neurogenic male LUTS)

Principles of Diagnostic Workup for BPH

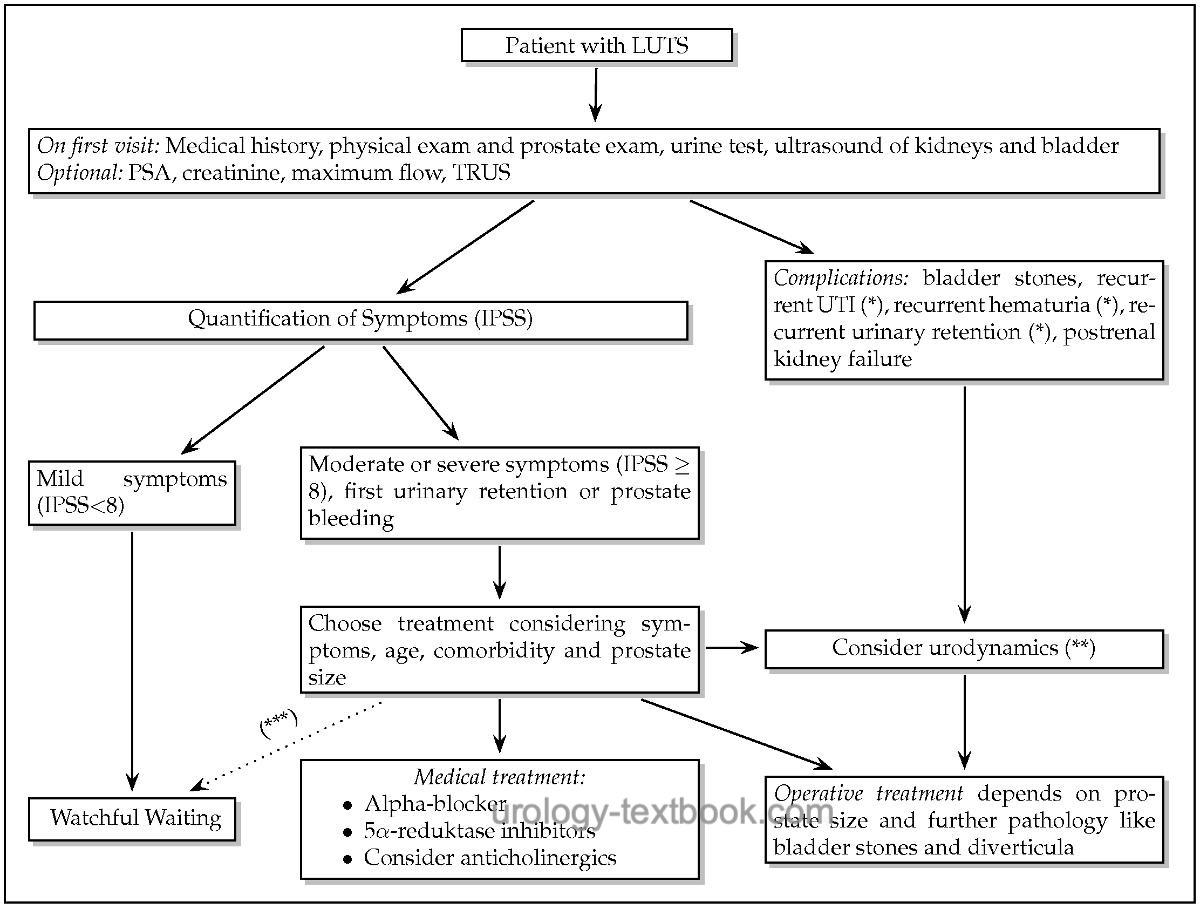

The diagnostic challenge is to clarify the cause of the patient's micturition symptoms. Only after a complete workup and exclusion of other diseases that cause micturition symptoms the diagnosis of BPO (symptomatic BPH) is justified. The isolated interpretation of the symptoms, the maximum flow, or the prostate volume is not sufficient to estimate the subvesical obstruction by the prostate. See fig. algorithm of BPH for diagnosis and treatment of LUTS due to BPH.

|

Medical History

The medical history is crucial for differential diagnosis of micturition symptoms:

Risk factors for urethral stricture:

Risk factors for urethral stricture are a history of urethritis, transurethral surgery, catheterization, or perineal trauma.

Risk factors for neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction:

Diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, stroke, after spinal and pelvic surgery.

Medication:

Sympathomimetics, anticholinergics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics may aggravate BPH symptoms.

Micturition diary:

A micturition diary is helpful in patients with nocturia to diagnose (nocturnal) polyuria caused by, e.g., diabetes, COPD, and heart failure.

Physical and prostate examination:

- Meatal stenosis?

- Phimosis?

- Prostate size? Prostate cancer?

- Anal sphincter tone?

- Saddle anesthesia?

- Paralysis?

Quantification of BPH symptoms:

The IPSS questionnaire is used to quantify symptoms.

Laboratory Studies in BPH

Urine Analysis:

Urine analysis microscope (urine sediment) or with urine test strips. Consider a urine culture in patients with leukocyturia.

Serum creatinine:

Creatinine testing should be done to exclude postrenal kidney failure.

PSA:

PSA testing helps to differentiate between BPH and prostate cancer. It is used in patients with a life expectancy of over ten years. Consider a prostate biopsy for pathological PSA concentrations. For a detailed discussion of PSA-based prostate cancer screening see section screening prostate cancer. BPH may also be responsible for elevated PSA concentrations. The PSA concentration correlates with the prostate size in symptomatic men and is predictive of the progression of BPH.

Further Testing

Maximum Flow Rate:

A maximum flow rate below 10 ml/s is typical for symptomatic BPH; a maximum flow rate >15 ml/s should raise doubts about diagnosing BPH needing surgical treatment. Unfortunately, uroflowmetry contributes little to the differential diagnosis between subvesical obstruction and bladder dysfunction. The micturition volume should be >150 ml for a meaningful uroflowmetry.

Ultrasound Imaging in BPH:

- Bladder ultrasound imaging: look for detrusor thickness, bladder stones or bladder diverticula.

- Postvoid residual urine? The significance of residual urine in managing BPH patients is controversial. There are high intra-individual differences in residual urine. It is not proven, if residual urine is a cause of recurrent urinary tract infections. Most probable, residual urine correlates with detrusor weakness rather than with subvesical obstruction. Normal values or values to indicate surgery or to prognose failure of conservative therapy are lacking.

- Prostate ultrasound imaging: transabdominal ultrasound or transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) is used to measure prostate size. The prostate is measured in the sagittal plane (length) and horizontal plane (width and depth), and the prostate volume is calculated using the formula:

V (prostate) = length × width × depth × 0.52 - Renal ultrasound imaging: Hydronephrosis?

|

|

|

Urodynamics in BPH:

Uroflowmetry is part of the basic diagnostic workup. Further urodynamic testing (cystometry) is reserved for unclear cases, particularly before invasive therapy or after failure of medical treatment. The EAU guidelines recommend cystometry for patients with LUTS and a maximum flow rate >15 ml/s, suspected neurogenic bladder dysfunction without subvesical obstruction, residual urine over 300 ml, men under 50 and over 80 years of age. Despite intensive urodynamic testing, almost 10% of patients still have persisting complaints after surgical treatment for proven subvesical obstruction.

Cystoscopy:

Cystoscopy is indicated for hematuria and to exclude urethral stricture, bladder stones, bladder diverticula, or bladder cancer. Endoscopic features of BPH are a large median lobe, bladder bar, kissing lateral prostate lobes, bladder trabeculation, and pseudodiverticula. The endoscopic picture cannot predict the need for surgical treatment [fig. cystoscopy of an obstructive prostate]. Cystoscopy should not be used for deciding whether an invasive therapy is necessary, but cystoscopy helps plan surgical treatment (TURP or simple prostatectomy).

|

Kissing lateral lobes in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): cystoscopy (view from the colliculus seminalis in the direction bladder). |

Radiological Imaging in BPH

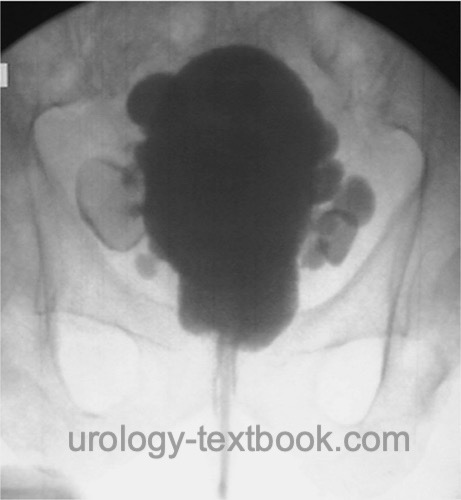

Intravenous Urogram:

IVU has long been standard for evaluating the upper urinary tract before surgical treatment in BPH. IVU reliably identifies hydronephrosis, bladder diverticula, residual urine, and bladder stones [fig. intravenous urogram in BPH]. The intravenous contrast medium may cause serious complications in 0.1%. As an alternative, combining an abdominal X-ray, sonography of the kidneys and bladder and the serum concentration of creatinine concentration offers the same diagnostic power to detect complications from BPH without any side effects.

|

Retrograde Urethrogram:

A retrograde urethrogram is indicated, if urethral stricture is suspected.

Cystography in BPH

Cystography is used for imaging of bladder diverticula or bladder stones [fig. cystography in BPH].

|

| BPH symptoms | Index | BPH treatment |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Andriole u.a. 2004 ANDRIOLE, G. L. ;

ROEHRBORN, C. ; SCHULMAN, C. ; SLAWIN, K. M. ;

SOMERVILLE, M. ; RITTMASTER, R. S.:

Effect of dutasteride on the detection of prostate cancer in men with

benign prostatic hyperplasia.

In: Urology

64 (2004), Nr. 3, S. 537–41; discussion 542–3

Burnett und Wein 2006 BURNETT, A. L. ; WEIN,

A. J.:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care: what you need to know.

In: J Urol

175 (2006), Nr. 3 Pt 2, S. S19–24

Chapple 2004 CHAPPLE, C. R.:

Pharmacological therapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary

tract symptoms: an overview for the practising clinician.

In: BJU Int

94 (2004), Nr. 5, S. 738–44

DGU Guideline, “S2e Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Benignen Prostatasyndroms (BPS).,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/043-034l_S2e_Diagnostik_Therapie_benignes_Prostatasyndrom_2023-04.pdf

Donovan u.a. 2000 DONOVAN, J. L. ; PETERS,

T. J. ; NEAL, D. E. ; BROOKES, S. T. ; GUJRAL,

S. ; CHACKO, K. N. ; WRIGHT, M. ; KENNEDY, L. G. ;

ABRAMS, P.:

A randomized trial comparing transurethral resection of the prostate,

laser therapy and conservative treatment of men with symptoms associated with

benign prostatic enlargement: The CLasP study.

In: J Urol

164 (2000), Nr. 1, S. 65–70

“EAU Guideline: Non-neurogenic Male LUTS,” Available: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/treatment-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts/.

Kopp, R. P.; Freedland, S. J. & Parsons, J. K.

Associations

of benign prostatic hyperplasia with prostate cancer: the debate continues.

Eur

Urol, 2011, 60, 699-700; discussion 701-2.

Ørsted, D. D.; Bojesen, S. E.; Nielsen, S. F. &

Nordestgaard, B. G.

Association of clinical benign prostate hyperplasia

with prostate cancer incidence and mortality revisited: a nationwide

cohort study of 3,009,258 men.

Eur Urol, 2011, 60,

691-698.

Parsons, J. Kellogg; Messer, Karen; White, Martha;

Barrett-Connor, Elizabeth; Bauer, Douglas C; Marshall, Lynn M; in Men

(MrOS) Research Group, Osteoporotic Fractures & the Urologic Diseases in

America Project

Obesity increases and physical activity decreases lower

urinary tract symptom risk in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men

study.

Eur Urol, 2011, 60, 1173-1180.

Reich u.a. 2006 REICH, O. ; GRATZKE, C. ;

STIEF, C. G.:

Techniques and long-term results of surgical procedures for BPH.

In: Eur Urol

49 (2006), Nr. 6, S. 970–8; discussion 978

Uygur u.a. 1998 UYGUR, M. C. ; GUR, E. ;

ARIK, A. I. ; ALTUG, U. ; EROL, D.:

Erectile dysfunction following treatments of benign prostatic

hyperplasia: a prospective study.

In: Andrologia

30 (1998), Nr. 1, S. 5–10

Deutsche Version: Diagnostik der benignen Prostatahyperplasie

Deutsche Version: Diagnostik der benignen Prostatahyperplasie