You are here: Urology Textbook > Prostate > BPH > Treatment algorithm

Treatment Algorithm and Medication for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: definitions, epidemiology and etiology

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: signs and symptoms

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: diagnosis

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: treatment algorithm

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia: surgical treatment

Review literature: (Burnett und Wein, 2006) (DGU guideline) (EAU guideline: Non-neurogenic male LUTS)

Basic Principles of BPH Therapy

- Watchful Waiting: Watchful Waiting is possible if surgery is unnecessary and the patient accepts his (moderate) symptoms.

- Medical treatment: is indicated for significant and disturbing symptoms and if surgical therapy is not needed (see below). The following drug classes for treating BPH are available; some drugs may be combined: herbal extracts, alpha blockers, 5α-reductase inhibitors, anticholinergics, β3 adrenergic receptor agonists, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors.

-

Surgical treatment of BPH: insufficient medical therapy, postrenal kidney failure, recurrent urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infections, recurrent hematuria, and significant bladder diverticula are indications for surgery. Standard surgical techniques are:

- Small prostate volume (below 40 ml): transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP), transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), or laser vaporization of the prostate.

- Medium prostate volume (40–100 ml): TURP, endoscopic enucleation of the prostate (EEP), or laser vaporization of the prostate.

- Large prostate volume (>75 ml): open or endoscopic enucleation of the prostate. If the treatment of a bladder diverticulum or large bladder stones is necessary, an open prostatectomy may be useful even with a smaller prostate volume.

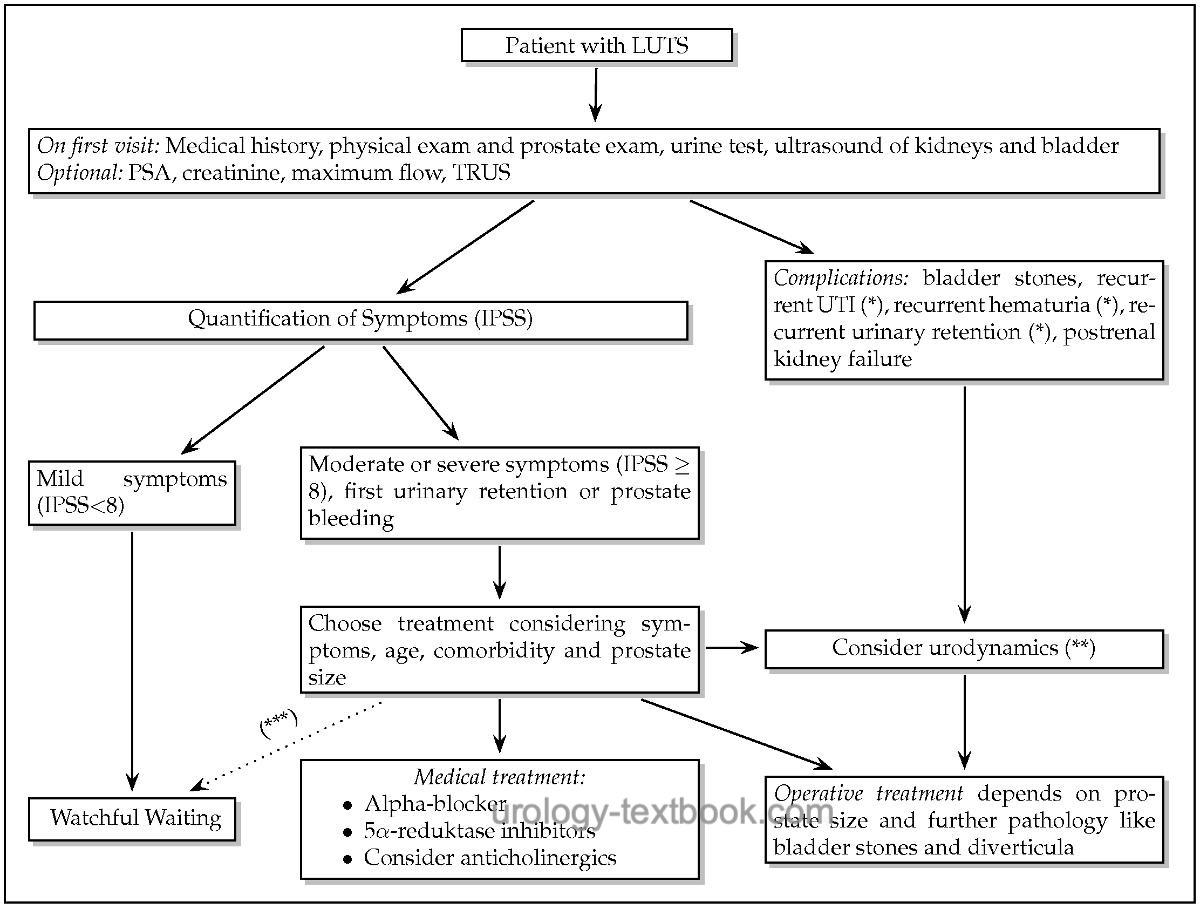

Algorithm for Initial Diagnosis and Treatment of Men with LUTS due to BPH

|

Watchful waiting in BPH

Watchful waiting in BPH is possible if there is no need for surgery and the patient accepts his (moderate) symptoms. 40% of the patients initially assigned to watchful waiting experience improvement of symptoms. 10–27% of the patients are going to have surgery for disease progression; risk factors are prostate volume (>40 ml), PSA concentration (>3.2 mg/ml), and a high IPSS.

Alpha Blockers for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Alpha blockers are the drugs of first choice to treat LUTS due to BPH. Numerous randomized trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the alpha blocker listed below. Furthermore, an alpha blocker should be given to support a trial without a catheter after urinary retention. See also the section pharmacology and side effects of alpha blocker.

Tamsulosin:

The dosage of tamsulosin is 0.4 mg 1-0-0 p.o. A low starting dosage is unnecessary. The OCAS galenic (Oral Controlled Absorption System) enables dosing independent from meals.

Alfuzosin:

The dosage of alfuzosin is 2.5 mg 1-1-1 or 5 mg 1-0-1 p.o. A low starting dosage is unnecessary. The sustained-release galenic enables a single dose of 5–10 mg 1-0-0 p.o.

Silodosin:

Silodosin is a new selective alpha blocker with few side effects on the cardiovascular system. The dosage is 8 mg 0-0-1 p.o. A dose reduction to 4 mg is necessary in chronic kidney disease. A low starting dosage is unnecessary.

Terazosin:

Terazosin is a drug of second choice because of its side effects, but it may benefit patients with arterial hypertension. The dosage of terazosin must start with a low dose in the evening before bedtime (1 mg 0-0-1 p.o.) to avoid side effects on arterial blood pressure. The dose may be increased weekly to 2 mg, 5 mg, or 10 mg once daily to achieve the desired improvement of symptoms.

Doxazosin:

Doxazosin is a drug of second choice because of its side effects, but it may benefit patients with arterial hypertension. The dosage of doxazosin must start with a low dose in the evening before bedtime (1 mg 0-0-1 p.o.) to avoid side effects on arterial blood pressure. The dose may be increased weekly to 2 mg, 5 mg, or 10 mg once daily to achieve the desired improvement of symptoms.

Comparison of Alpha Blocker:

The analysis of placebo-controlled trials shows that terazosin and doxazosin are more effective, but this leads to a higher rate of side effects (e.g., dizziness, weakness, postural hypotension). The advantages of alfuzosin and tamsulosin are reduced side effects and the lack of necessity for dose titration.

BPH and Accompanying Arterial Hypertension:

Alpha blockers for arterial hypertension proved inferior to beta-blocker and ACE inhibitors (ALLHAT, 2000). Therefore, alpha blockers are not recommended as first-line treatment for arterial hypertension. This also applies to patients with arterial hypertension and BPH: it is more beneficial to treat arterial hypertension with a drug of first choice and to treat BPH with a selective alpha 1A-blocker.

5α-Reductase Inhibitors for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is the main androgen for the prostate; it is converted from testosterone by the 5α-reductase. Finasteride is a competitive inhibitor of the 5α-reductase type 2, leading to lower concentrations of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the prostate. DHT is the only effective androgen on the prostate; thus, a selective androgen deprivation of the prostate is possible. Dutasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor that acts on type 1 and 2 isoenzymes of the 5α-reductase.

The consequence of 5α-reductase inhibition is the shrinkage of the prostate (7–13 ml in 12 months), improvement of LUTS (decreasing IPSS), and improved urinary flow (maximum flow 0.6–1.6 ml/s better than placebo). The mechanism of action is slow; a significant clinical effect can be expected after a treatment period of 1 year. The larger the prostate, the greater the therapeutic effect. After five years of treatment, there is a significant risk reduction for urinary retention (3% vs. 7%), gross hematuria, or the need for TURP (5% vs. 10%) (McConnell et al., 1998). The shrinking of the prostate also decreases the PSA concentration (up to 50%).

Pharmacokinetics and Side Effects of 5α-Reductase Inhibitors

5α-reductase inhibitors are well tolerated, and the safety of the drugs was documented in several long trials; for details, see sections finasteride and dutasteride. Both substances reduce the incidence of prostate cancer if given over several years (Andriole et al., 2004). This led to the initiation of prostate cancer prevention trials, such as the REDUCE trial [see section prevention of prostate cancer].

Dosage of 5α-Reductase Inhibitors:

Finasteride 5 mg p.o. once daily, dutasteride 0,5 mg p.o. once daily.

Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for BPH

Smooth muscle cells of the prostate and urinary bladder also express type 4 and type 5 phosphodiesterase. Randomized trials show that treatment with tadalafil relieves BPH symptoms (Laydner et al., 2011). The therapeutic effect of tadalafil is comparable to tamsulosin, and erectile function improves (Oelke et al., 2012). Tadalafil has been approved for the therapy of BPH since 2012, and the dosage is 5 mg once daily.

Anticholinergics for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Storage symptoms without significant residual urine may be treated with anticholinergic drugs. Trials have shown that there is only a low risk for urinary retention. Alternatively, newly approved β3 adrenergic receptor agonists such as mirabegron can be used in cases of intolerance or lack of efficacy. Anticholinergic drugs may be combined with an alpha blocker if there is significant obstruction. The combination therapy increases the side effects.

Treatment of Nocturia

Nocturia is a distressing symptom that BPH can cause, but also numerous other conditions, see section nocturia. It is essential to rule out internal medicine diseases causing nocturia before starting treatment: control diuretic medication and exclude cardiac, pulmonary, neurological, or metabolic causes of nocturia.

- Micturition diary: to diagnose nocturnal polyuria and bladder storage disorders.

- Behavioral therapy: optimizing sleep hygiene and refraining from evening fluids and alcohol is important.

- Urological treatment: conservative or, if necessary, surgical therapy of BPH for voiding symptoms or residual urine. Therapy of overactive bladder in case of storage symptoms.

- Desmopressin is an option if nocturia persists despite the above-mentioned measures. The dosage of desmopressin is 50 μg before bedtime for men and 25 μg for women (Han et al., 2017). For pharmacology, contraindications, and side effects, see desmopressin.

Drug Combinations for the Treatment of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Sound drug combinations are the administration of an alpha blocker for rapid symptom improvement and a 5α-reductase inhibitor for long-term prostate volume reduction. The efficiency and safety of the combination was demonstrated in randomized trials. The alpha blocker may be stopped in the further course of the treatment.

Another useful combination is the administration of anticholinergics for storage symptoms and an alpha blocker for voiding symptoms.

Phytotherapeutic Drugs for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

Mono extracts or combinations of plant extracts from Sabal serrulata (dwarf palm), Serenoa repens (saw palmetto), Pygeum africanum (African plum), beta-Sitosterone from Hypoxis rooperi (African grass), Secale cereale (rye) and many more are available over the counter. Suspected mechanisms of action include the inhibition of 5α-reductase (Serenoa repens), the inhibition of growth factors (Pygeum africanum), promotion of apoptosis (Serenoa repens), anti-inflammatory effects, and placebo effects. Only a few well-structured randomized trials indicate a moderate effect of plant extracts; the effect of Serenoa repens (Saw Palmetto) is documented best. Trials documenting the long-term efficiency and safety of plant extract are not available.

| BPH diagnosis | Index | BPH Surgery |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Andriole u.a. 2004 ANDRIOLE, G. L. ;

ROEHRBORN, C. ; SCHULMAN, C. ; SLAWIN, K. M. ;

SOMERVILLE, M. ; RITTMASTER, R. S.:

Effect of dutasteride on the detection of prostate cancer in men with

benign prostatic hyperplasia.

In: Urology

64 (2004), Nr. 3, S. 537–41; discussion 542–3

Burnett und Wein 2006 BURNETT, A. L. ; WEIN,

A. J.:

Benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care: what you need to know.

In: J Urol

175 (2006), Nr. 3 Pt 2, S. S19–24

Chapple 2004 CHAPPLE, C. R.:

Pharmacological therapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia/lower urinary

tract symptoms: an overview for the practising clinician.

In: BJU Int

94 (2004), Nr. 5, S. 738–44

DGU Guideline, “S2e Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Benignen Prostatasyndroms (BPS).,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/043-034l_S2e_Diagnostik_Therapie_benignes_Prostatasyndrom_2023-04.pdf

Donovan u.a. 2000 DONOVAN, J. L. ; PETERS,

T. J. ; NEAL, D. E. ; BROOKES, S. T. ; GUJRAL,

S. ; CHACKO, K. N. ; WRIGHT, M. ; KENNEDY, L. G. ;

ABRAMS, P.:

A randomized trial comparing transurethral resection of the prostate,

laser therapy and conservative treatment of men with symptoms associated with

benign prostatic enlargement: The CLasP study.

In: J Urol

164 (2000), Nr. 1, S. 65–70

“EAU Guideline: Non-neurogenic Male LUTS,” Available: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/treatment-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts/.

Kopp, R. P.; Freedland, S. J. & Parsons, J. K.

Associations

of benign prostatic hyperplasia with prostate cancer: the debate continues.

Eur

Urol, 2011, 60, 699-700; discussion 701-2.

Ørsted, D. D.; Bojesen, S. E.; Nielsen, S. F. &

Nordestgaard, B. G.

Association of clinical benign prostate hyperplasia

with prostate cancer incidence and mortality revisited: a nationwide

cohort study of 3,009,258 men.

Eur Urol, 2011, 60,

691-698.

Parsons, J. Kellogg; Messer, Karen; White, Martha;

Barrett-Connor, Elizabeth; Bauer, Douglas C; Marshall, Lynn M; in Men

(MrOS) Research Group, Osteoporotic Fractures & the Urologic Diseases in

America Project

Obesity increases and physical activity decreases lower

urinary tract symptom risk in older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men

study.

Eur Urol, 2011, 60, 1173-1180.

Reich u.a. 2006 REICH, O. ; GRATZKE, C. ;

STIEF, C. G.:

Techniques and long-term results of surgical procedures for BPH.

In: Eur Urol

49 (2006), Nr. 6, S. 970–8; discussion 978

Uygur u.a. 1998 UYGUR, M. C. ; GUR, E. ;

ARIK, A. I. ; ALTUG, U. ; EROL, D.:

Erectile dysfunction following treatments of benign prostatic

hyperplasia: a prospective study.

In: Andrologia

30 (1998), Nr. 1, S. 5–10

Deutsche Version: Therapie der benignen Prostatahyperplasie

Deutsche Version: Therapie der benignen Prostatahyperplasie

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.