You are here: Urology Textbook > Kidneys > Nephrolithiasis

Medical and Surgical Treatment of Kidney and Ureteral Stones

- Nephrolithiasis: Etiology and Epidemiology

- Diagnosis of Nephrolithiasis and Renal Colic

- Treatment of Kidney and Ureteral Stones

|

Renal Colic

Acute pain medication:

The first choice medication is NSAID. If insufficient or for patients with contraindications, opioids like piritramid or morphine are recommended. If pain is uncontrolled by pain medication, ureteral splinting or nasal desmopressin (to reduce diuresis, off-label) are an option. Further treatment depends on stone size and location; see table Treatment options for urolithiasis.

- Diclofenac: 37.5 mg slowly i.v. (0.5 mg/kg for children). Maximum daily dosage 150 mg (2 mg/kg for children).

- Ketorolac: 30 mg slowly i.v. (0.5 mg/kg for children). Maximum daily dosage 120 mg (2 mg/kg for children).

- Metamizole: 1–2 g i.v. over 15–30 min infusion. Maximum daily dosage 6 g (70 mg/kg body weight).

- Piritramid: 7,5 mg slowly i.v. In children 0,05–0,1 mg/kg body weight i.v. Repeat dosage after 6 hours as a subcutaneous injection.

- Morphine: first dosage 10 mg slowly i.v. (0,1 mg/kg body weight), repeat dosage as a subcutaneous injection.

Conservative Therapy – Medical Expulsive Therapy

Ureteral stones:

Ureteral stones <5 mm have a 75% chance of spontaneous passage. For ureteral calculi >5 mm, the chance of a spontaneous passage drops significantly to 62%. The more distal the stone, the more likely the chance of spontaneous passage: passage rates are 49%, 58%, and 68% for proximal, middle, and distal thirds (Yallappa et al., 2018). Almost all calculi that pass spontaneously perish within six weeks. Contraindications for conservative therapy of the ureteral stone are infected hydronephrosis, forniceal rupture, therapy-refractory colic pain, and a low probability of spontaneous passage.

Medical expulsive therapy:

Cornerstones of medical expulsive treatment are the prescription of sufficient pain medication, education about the possibility of recurrent colic, and possible complications which warrant invasive therapy.

- Sufficient fluid intake and physical activity.

- Diclofenac 50 mg 1-0-1 as pain medication and against ureteral wall edema.

- For prevesical stone location, off-label prescription of α blocker (tamsulosin, alfuzosin) alleviates pain and accelerates the stone passage. Other effective drugs without approval or sufficient trials: nifedipine and Rowatinex.

- Prescription of additional pain medication to treat renal colic: e.g., metamizole, acetaminophen, or opioids.

- Anticholinergics (e.g., butylscopolamine) had no effect in several studies (Kallidonis et al., 2011).

Calyceal kidney stones:

Calyceal kidney stones under 5 mm should not be treated; they may pass spontaneously. Larger calyceal kidney stones may be observed with annual ultrasound imaging: invasive therapy is necessary for size progression or symptoms. Observation of kidney stones is not an option in pilots, truck drivers, or comparable professional groups. The clinical significance of small residual stones after ESWL is controversial; they are often observed. Age and comorbidity are important factors regarding the treatment decision.

Treatment of Upper Urinary Tract Obstruction

Emergency indications:

Uncontrolled pain due to renal colic, forniceal rupture, urinoma, infected hydronephrosis, urosepsis, or significant acute renal failure.

Methods of decompression:

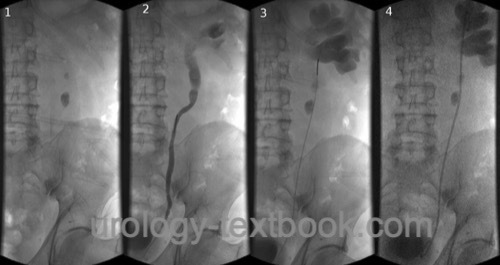

Options are retrograde pyelography and placement of an MJ or DJ ureteral stent [fig. DJ placement], or percutaneous nephrostomy.

|

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

Indications:

ESWL is a treatment option for kidney stones with a diameter of 0.5–2 cm, for stones in the two upper thirds of the ureter, and possibly also for distal ureteral stones, see table Treatment options for urolithiasis.

Procedure and complications:

See section Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy ESWL.

Results:

Averaged for all stone locations, about 73% of the patients are stone-free after three months. Effective medical expulsive therapy is essential for the success of ESWL since all fragments have to pass the ureter.

Calyceal kidney calculi:

Stone clearance can be achieved in up to 40–78% for lower calyceal stones. A higher success rate of 64–85% is possible for mid and upper calyceal stones. The stone clearance depends on the diameter and length of the calyceal necks and the angle between the ureter and the calyceal group.

Calculi in renal pelvis and ureter:

Stone clearance up to 90%.

Predictors for a successful ESWL:

Calculi in the upper and middle group of calyces, calculi with an irregular surface and heterogeneous internal structure, and struwite stones.

Predictors for unsuccessful ESWL:

Stones in the lower calyx, calyceal kidney stones with narrow and long calyceal neck, brushite stones, with smooth surface and homogeneous internal structure, stone density over 970 HU, considerable skin-to-stone distance >10 cm. Cystine stones are unsuitable for therapy with ESWL.

Ureterorenoscopy (URS)

Indications:

For ureteral and renal calculi, see the table Treatment options for urolithiasis. With increasing improvement of the flexible instruments and stone disintegration technology (RIRS: retrograde intrarenal surgery), proximal ureteral stones and kidney stones up to 15 mm in size can also be treated with URS.

|

Surgical technique and complications:

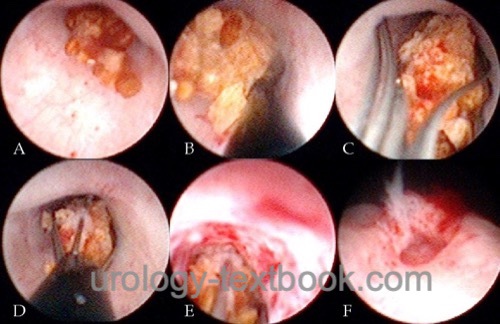

See section ureterrenoscopy. Small ureteral stones are extracted with a Dormia basket [fig. URS stone extraction] or a forceps. Larger stones can be disintegrated using laser energy [fig. URS laser stone disintegration] or mechanical lithotriptors (where Laser is not available). If proximal ureteral stones dislocate into the renal pelvis during lithotripsy and flexible URS is unavailable, further treatment is possible with ESWL (push and smash).

|

|

Results:

90% of distal and 60% of proximal ureteral stones can be removed by URS in a single session. Using newer technology (flexible URS with holmium laser), treatment success of over 90% is published for proximal ureteral stones (depending on size).

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PNL)

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is an endoscopic minimally invasive procedure for the removal of kidney stones 1 cm or larger. Abbreviations: PCNL or PNL. Synonym: percutaneous nephrolitholapaxy.

Indication:

Renal stones over 2 cm in size, lower pole calyceal stones from 10 mm in size, and kidney stones refractory to treatment with ESWL. With the introduction of smaller instruments (Mini-PNL) and better stone disintegration technology, the morbidity of PNL has been reduced, and more kidney stones will be treated by PNL at the expense of ESWL [see table Treatment options for urolithiasis].

Surgical technique and complications:

See section Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PNL).

Results:

The treatment success of a single session is around 90%, highly dependent on caliceal anatomy and stone burden. The fragmented stone material is removed during the procedure (in contrast to lithotripsy with URS or ESWL).

Laparoscopic or Open Stone Surgery

Rare indications for stone surgery are treating refractory urinary stones after frustrating endoscopy or accompanying diseases (UPJ obstruction, renal abscess, renal tumors). Checking kidney function is mandatory before stone surgery. In principle, all indications listed below can be performed using laparoscopy, but considerable laparoscopic expertise is required.

- Nephrolithotomy: for large staghorn calculi, if a one-stage procedure is desired (e.g., children). UPJ obstruction can be corrected with nephrolithotomy in a single operation; the same is true for calyceal stenosis or calyceal diverticula.

- Ureterotomy: an option for very large ureteral calculi.

- Nephrectomy: for a nonfunctioning kidney.

Basic Measures of Stone Recurrence Prevention

Without the presence of risk factors [table risk factors for stone recurrence], the following basic measures are recommended to prevent the recurrence of nephrolithiasis (Siener et al., 2006):

Fluid intake:

Increase the fluid intake up to a diuresis of >2.0 l. The increased fluid intake should be distributed evenly throughout the day, drinking during the night is necessary. The specific weight of urine should be less than 1.010 g/ml.

The fluid intake should be urine neutral: the beverages should not change the quantitative composition of urine (electrolytes, pH). Suitable beverages are mineral waters with a low content of mineral salts and bicarbonate, tap water, herbal tea, and diluted fruit juices. Unsuitable drinks are sugary lemonades, too much coffee or black tea, and alcoholic drinks.

Diet:

A mixed balanced diet with a reduced amount of animal protein (1 g/kg body weight) is recommended. Fruit and vegetable intake should be encouraged, but vegetables containing oxalic acid, such as spinach, chard, or rhubarb, should be avoided. Calcium intake should not be restricted; the goal is the intake of 1000 mg of calcium/day. Patients should avoid alcohol.

Body weight:

Obesity and the associated nutritional patterns are risk factors for recurrent nephrolithiasis. The goal is a gentle, long-term reduction in body weight with the diet mentioned above and combining the measures with physical exercise. Fasting and unbalanced diets are not helpful.

Pharmacological Recurrence Prevention

The fundation of successful pharmacological metaphylaxis is the exact metabolic diagnosis and the patient's compliance to follow above mentioned basic measures to prevent recurrences. Frequent recurrences will occur in 25% of stone patients. Table risk factors for stone recurrence lists risk groups that benefit from pharmacological metaphylaxis.

Calcium oxalate stones:

Alkali citrates, or sodium bicarbonate, prevent calcium oxalate stones. Both substances reduce citrate reabsorption in the proximal tubule and thus improve the inhibitory properties of the urine against stone formation. In the following specific metabolic constellations, additional medication is recommended (Straub et al., 2005) (EAU Guidelines):

- Hypercalciuria 5–8 mmol/d: Alkali citrates 9–12 g/d, alternatively sodium bicarbonate 1,5 g 1-1-1.

- Hypercalciuria >8 mmol/d: alkali citrates 9–12 g/d, alternatively sodium bicarbonate 1,5 g 1-1-1 p.o. Additional administration of thiazide diuretics, which reduce calciuria: hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d, if necessary increase to 50 mg/d.

- Hypocitraturia <2,5 mmol/d: alkali citrates 9–12 g/d.

- Hyperoxaluria 0,5–1 mmol/d: low-oxalate diet, calcium intake 1000 mg/d, and magnesium intake 200–400 mg/d (not in chronic kidney disease) distributed with the meals.

- Hyperoxaluria >1 mmol/d: primary hyperoxaluria is likely; treatment should be delegated to a specialized center. High urine dilution, pyridoxine (Vitamin B6), alkali citrates, and magnesium are used. In hyperoxaluria type 1, lumasiran can be used to inhibit the expression of a liver enzyme (glycolate oxidase) via RNA interference; the drug has been available as an orphan drug since 2020. Despite all drug efforts, terminal kidney failure may develop.

- Hyperuricosuria >4 mmol/d: low-purine diet, alkali citrates 9–12 g/d, allopurinol 100 mg/d. Increase allopurinol dosage to 300 mg/d for patients with serum concentration of uric acid above 380 μmol/l and sufficient kidney function.

- Hypomagnesuria <3 mmol/d: magnesium intake 200–400 mg/d (not in chronic kidney disease) distributed with the meals.

Calcium phosphate stones:

Causes of calcium phosphate stones are hyperparathyroidism, renal tubular acidosis, and urinary tract infections.

- Hyperparathyroidism: treatment of choice is parathyroidectomy.

- Renal tubular acidosis: alkali citrates 9–12 g/d, alternatively sodium bicarbonate 1,5 g 1-1-1 p.o. Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d for hypercalciuria over 8 mmol/24 h urine, if necessary increase to 50 mg/d.

- Infection stones: see next section.

- Unknown cause: if hyperparathyroidism, infection stone, or renal tubular acidosis have been excluded, urine acidification with L-methionine 200–500 mg 1-1-1 (target pH 5.8–6.2) is recommended. Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/d for hypercalciuria over 8 mmol/24 h urine, if necessary increase to 50 mg/d.

Infection stones:

Basic urine (pH>7) in the urine pH is common. Complete stone removal, appropriate long-term antibiotic therapy, urinary dilution, and urine acidification with L-methionine 200–500 mg 1-1-1 (target pH of urine 5.8–6.2) are cornerstones for successful therapy.

Uric acid stones:

Main causes of urinary stone formation are hyperuricosuria and a constant low urine pH (below 6, acidic arrest). For prevention, a low-purine diet, urinary dilution, and alkalization of the urine by alkali citrates or sodium bicarbonate (target urine pH 6.2–6.8) are important. Residual uric acid stones can be treated with chemolysis; a urine pH of 7.0–7.2 is necessary. In addition, allopurinol 100 mg/d is prescribed to reduce hyperuricosuria and hyperuricemia. If insufficient (hyperuricemia >380 μmol/l) and sufficient kidney function, increase the allopurinol dosage to 300 mg/d.

Cystine stones:

Increase diuresis >3.5 l in adults, alkalization of the urine with alkaline citrates (target pH above 7.5), reduction in animal protein, ascorbic acid up to 5 g daily. With cystine secretion over 3 mmol/day despite above mentioned measures, oral therapy with tiopronin is indicated. Initially 250 mg 1-0-1, the dosage can be increased up to 2 g/day.

Xanthine or 2.8 dihydroxyadenine stones:

Increase diuresis, low-purine diet. Consider allopurinol for 2.8 dihydroxyadenine stones.

| Renal colic | Index | Oncocytoma |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Coe u.a. 2005 COE, F. L. ; EVAN, A. ;

WORCESTER, E.:

Kidney stone disease.

In: J Clin Invest

115 (2005), Nr. 10, S. 2598–608

Kallidonis, P.; Liourdi, D. & Liatsikos, E.

Medical

treatment for renal colic and stone expulsion

Eur Urol Suppl, 2011,

10, 415-422.

Moe 2006 MOE, O. W.:

Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management.

In: Lancet

367 (2006), Nr. 9507, S. 333–44

R. Siener und A. Hesse.

[modern general metaphylaxis of stone disease. new risks, new

evidence, new recommendations].

Urologe A, 45 (11): 1392, 1394–1392, 1398,

Nov 2006.

M. Straub, W. L. Strohmaier, W. Berg, B. Beck, B. Hoppe, N. Laube, S. Lahme,

M. Schmidt, A. Hesse, und K. U. Koehrmann.

Diagnosis and metaphylaxis of stone disease. consensus concept of the

national working committee on stone disease for the upcoming german

urolithiasis guideline.

World J Urol, 23 (5): 309–323, Nov 2005.

S. Yallappa et al., “Natural History of Conservatively Managed Ureteral Stones: Analysis of 6600 Patients.,” Journal of endourology, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 371–379, 2018.

Deutsche Version: Epidemiologie und Ursachen der Nephrolithiasis

Deutsche Version: Epidemiologie und Ursachen der Nephrolithiasis