You are here: Urology Textbook > Penis > Penile Cancer

Penile Cancer

Carcinoma of the penis is most common squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and originates from the epithelium of the glans or inner prepuce. SCC of the penis has pathologic and clinical features in common with SCC of other sites such as the cervix, anus, and oropharynx. Guidelines: (EAU Guidelines Penile Cancer), (S3-Leitlinie Peniskarzinom).

Epidemiology of Penile Cancer

Penile carcinoma is rare in the countries of the Western world. In Germany, approximately 950 new cases were recorded in 2014, corresponding to an incidence of 2 per 100.000 men or 1 per 100.000 inhabitants. The peak age of onset of the disease is over 60 years. Penile carcinoma is more common in Asia (e.g., China, Vietnam), Africa (e.g., Uganda), and also in America (e.g., Mexico, Puerto Rico), with incidence rates up to 8 per 100.000 inhabitants (Colberg u.a., 2018).

Etiology and Pathogenesis of Penile Carcinoma

Circumcision:

Circumcision performed after birth is an effective preventive measure against the development of penile carcinoma. The incidence of penile carcinoma in Israel is 0.04 per 100.000. Circumcision during puberty leads to only a minor reduction in incidence; in adulthood, circumcision no longer shows a preventive effect.

Smegma retention and chronic balanitis:

Smegma retention and chronic balanitis is a risk factor for penile cancer. Improved hygiene accounts for a halved incidence over the last 50 years.

Human papillomavirus:

HPV is detectable in 30–50% of penile carcinomas, and the number is even more significant in warty tumors and CIS. HPV plays a less critical role in the development of penile carcinoma than in female cervical carcinoma. See section condylomata acuminata for a detailed description of epidemiology and molecular mechanisms.

Smoking:

Smoking is a relevant risk factor for penile carcinoma: approximately fivefold relative risk (dose-dependent).

Lichen sclerosus:

Lichen sclerosus is a risk factor probably due to common risk factors.

Pathology and TNM Tumor Stages of Penile Cancer

TNM Tumor Stages [UICC 2017]

T:

Primary tumor.

- Tis: Carcinoma in situ (penile intraepithelial Neoplasia – PeIN).

- Ta: Non-invasive localized tumor, inclusive verrucous carcinoma.

- T1: Tumor invades subepithelial connective tissue.

- T1a: Without lymphovascular invasion, without perineural invasion, and not poorly differentiated.

- T1b: With lymphovascular invasion, with perineural invasion, or poorly differentiated.

- T2: Tumor invades corpus spongiosum, with or without infiltration of the urethra.

- T3: Tumor invades corpus cavernosum or tunica albuginea, with or without infiltration of the urethra.

- T4: Tumor invades other adjacent structures.

N:

Regional lymph nodes.

- N0: No palpable or enlarged (imaging) inguinal lymph nodes.

- N1: single palpable mobile enlarged inguinal lymph node (cN1) or metastasis in 1–2 inguinal lymph nodes (pN1)

- N2: multiple or bilateral palpable mobile enlarged inguinal lymph nodes (cN1) or metastasis in three or more inguinal lymph nodes (pN2)

- N3: fixed inguinal lymph node mass or enlarged pelvic lymph nodes (cN3) or pelvic lymph node metastasis (pN3) or extranodal tumor growth (pN3).

M:

Distant metastasis.

- M0: No distant metastasis.

- M1: Distant metastasis.

G:

Grading.

- G1: Well differentiated.

- G2: Moderately differentiated.

- G3/G4: Poorly differentiated or undifferentiated.

Gross Pathology

In most cases, penile carcinoma manifests at the glans, the sulcus coronarius, or the prepuce. The growth pattern is either exophytic or, less frequently, ulcerative.

Metastasis

Lymph node metastases are most common, with a probability of 30% at initial manifestation (depending on tumor stage). Less frequently (3%) and almost always accompanied by lymph node metastases, metastases develop in the lung, liver, bone, or CNS.

Histology

Non-HPV-related penile carcinomas (Over 50%):

- Classical squamous cell carcinoma: most common subtype, with or without keratinization. The prognosis depends on the grading.

- Verrucous squamous cell carcinoma: wartlike benign subtype, metastases only in exceptional cases.

- Papillary squamous cell carcinoma: benign subtype, metastases only in exceptional cases.

- Sarcomatoid squamous cell carcinoma: rare, aggressive subtype, early vascular metastasis.

- Adenosquamous squamous cell carcinoma: rare, early metastasis.

HPV-related penile carcinomas (Less than 50%):

- Basaloid squamous cell carcinoma: aggressive subtype with early lymphogenic metastasis.

- Condylomatous squamous cell carcinoma: warty benign subtype, metastases only in exceptional cases.

Rare forms:

Clear cell carcinoma originating from sweat glands, Paget disease of the penis, malignant melanoma, lymphoma, and metastases (Erbersdobler u.a., 2018).

Signs and Symptoms

In the early stages, penile carcinoma appears as a flat, raised redness, later an exophytic tumor develops. Less frequently, the tumor results in an ulceration [fig. penile cancer]. The preferred localization is the glans penis and distal prepuce.

If untreated, a locally progressive tumor growth develops with infiltration of the corpora cavernosa and the urethra (urinary retention) [fig. advanced penile cancer]. Signs of inguinal lymph node metastases are a non-painful lymph node enlargement or fixed inguinal mass. Infiltration of the iliac vessels can rarely cause fatal arterial hemorrhage. Distant metastases may develop in the lung, liver, bone, skin [fig. penile cancer skin metastases], and CNS.

Diagnosis of Penile Cancer

Tumor marker:

SCC (squamous cell carcinoma antigen) is elevated in 25% and may be used for follow-up.

Local tumor stage:

Physical examination can reliably detect the local tumor stage in small penile tumors, particularly to assess the infiltration of the urethra or corpora cavernosa. In larger tumors, supplementary sonography or MRI is helpful.

Biopsy:

A histological examination is necessary for the correct diagnosis. Further treatment decisions depend on grading and depth of infiltration. Small penile tumors are completely removed by wedge excision, see next section. Specimens are taken from the margins and tumor base for exact diagnosis. A partial excision biopsy of sufficient depth is performed to plan therapy for large penile tumors.

Lymph node status:

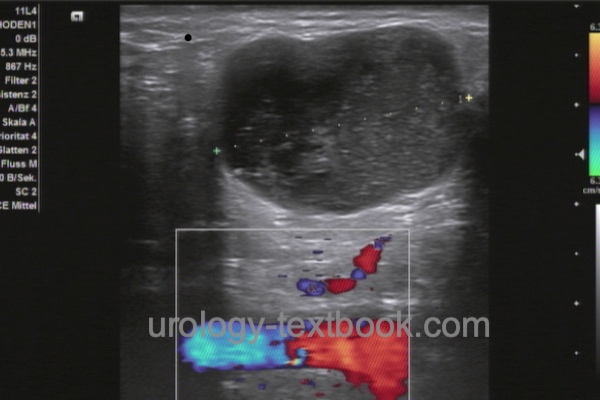

The minimum effort is palpation of the inguinal lymph nodes (localization, number, mobility). Cross-sectional imaging of the inguinal region and pelvis (CT, MRI, or PET-CT) is indicated in cases of lymphadenopathy, prior surgery, and obesity. All imaging modalities have the disadvantage of not detecting lymph node metastases without lymph node enlargement. 50% of patients with enlarged lymph nodes have metastases, and benign causes of lymph node enlargement are equally common [see section differential diagnosis of groin lumps]. Sonography of the inguinal lymph nodes can sometimes be helpful in differentiation [fig. benign lymphadenopathy and malignant lymphadenopathy]. Signs of malignant lymphadenopathy are a short-axis diameter of more than 10 mm, a round lymph node shape, inhomogeneous hypoechoic areas, lack of visualization of the echo-rich hilus, and an irregular boundary indicating extranodal growth.

|

|

Distant metastasis:

Perform CT or PET-CT (chest, abdomen, and pelvis) in cases of proven lymph node metastases and add bone scintigraphy in patients with systemic disease or elevated AP.

Differential Diagnosis

Numerous benign diseases can clinically mimic penile carcinoma; histological confirmation is necessary before radical therapy.

- Infections: Ulcus molle (chancroid), syphilis (chancre), herpes genitalis, lymphogranuloma venereum, granuloma inguinale, tuberculosis.

- Benign tumors: Condyloma acuminata, leiomyoma, lichen sclerosus.

- Premalignant lesions: Erythroplasia de Queyrat, Bowen disease, leukoplakia.

- Malignant tumors: Basal cell carcinoma, sarcoma, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, or malignant melanoma, overall rare.

Treatment of Penile Cancer

Treatment of the Primary Tumor

Treatment of Ta Tumors and CIS:

Lesions of the prepuce are treated with a complete circumcision. Lesions of the glans are treated with laser therapy after histological confirmation. Nd:YAG laser is a good option due to a depth effect by coagulation of 3–6 mm. A response rate of 100% is achievable for CIS, but the recurrence rate is 26%. Laser therapy of T1 and T2 penile carcinoma is insufficient; a reliable deep biopsy is essential for treatment planning.

"Glans resurfacing" is an alternative treatment option for flat lesions of the glans. Complete excision of the glans epithelium and subepithelium is performed in addition to circumcision. Deep biopsies of the underlying spongiosum tissue are done to verify complete tumor resection. The defect is covered with a skin graft (from the thigh). Functional results are favorable.

Another alternative therapy for penile CIS is topical therapy with imiquimod or 5-FU (off-label). Response rates of up to 57% have been reported. Due to the high recurrence rate, close follow-up must be ensured. In case of failure of topical therapy, the above-mentioned therapeutic procedures or glansectomy should be chosen.

Treatment of T1 Tumors:

Tumors of the prepuce are excised by complete circumcision. Smaller glans lesions are treated by wedge excision; a few millimeters are sufficient as a safety margin. For larger tumors, glansectomy is necessary; after excision, the defect is closed with skin from the penile shaft.

Treatment of T2 Tumors:

For penile tumors without infiltration of the corpus cavernosum, glansectomy is sufficient if a safety margin of 5 mm is possible. Partial penectomy is necessary in cases of infiltration of the corpus cavernosum; the safety margin should not be less than 0.5–1 cm. See the section partial penectomy for details of the surgical technique.

Treatment of T3–4 Tumors:

Partial penectomy or complete amputation with perineal urethrostomy is necessary, depending on the tumor location. The urinary stream should still be alignable by the patient after penis-preserving surgery. See section radical penectomy for surgical technique and complications. Reconstruction of the penis using a radial forearm flap with hydraulic penile prosthesis is an option, which is offered in a few centers to younger and sexually active patients.

Radiotherapy of the Primary Tumor:

Penile carcinoma is radiosensitive; radiotherapy is a treatment option for T1–2 penile carcinoma less than 4 cm in diameter. Appropriate patient selection can achieve good functional outcomes and organ preservation. The radiation dose is applied as either conformal radiotherapy (EBRT) or brachytherapy, and better clinical outcomes are published with brachytherapy (Crook et al., 2016). The recurrence rate is slightly higher than after surgical therapy, and potential local side effects (fistulas, strictures, glans necrosis) are disadvantages of radiotherapy.

Management of Regional Lymph Nodes

Indications for Diagnostic Inguinal Lymphadenectomy:

Complete surgical removal of the inguinal and iliac lymph nodes offers the only chance of a cure in the case of lymph node metastases. Since imaging cannot reliably detect lymph node metastasis, invasive lymph node sampling is recommended for patients with elevated risk for occult metastases: patients with pT1G2–3 and pT2–4 penile carcinoma. Diagnostic lymphadenectomy can be performed at the same time as the surgery of the primary tumor or later after obtaining the final histology of the primary tumor.

There is no indication for invasive lymph node staging in patients without enlarged lymph nodes and low-risk carcinoma (Ta, Tis, T1G1). The low probability of metastasis does not justify the spectrum of side effects of inguinal lymphadenectomy. Enlarged lymph nodes in low-risk tumors should be evaluated by excisional or fine-needle biopsy. In all cases without lymphadenectomy, close patient monitoring is necessary for early detection of lymphadenopathy.

Invasive lymph node staging is possible with modified inguinal lymphadenectomy or dynamic sentinel node biopsy. Prospective randomized trials comparing both techniques are unavailable; both techniques may miss metastatic disease (false negative).

Modified Inguinal Lymphadenectomy:

The modified inguinal lymphadenectomy (Catalona et al., 1988) reduces the dissection to the area superficial to the fascia lata and medial to the superficial epigastric vein and the great saphenous vein, which is also spared. Deep lymph nodes from the fossa ovalis are also removed. See section inguinal lymphadenectomy for surgical technique and complications. Intraoperatively suspicious lymph nodes may be examined by frozen section, or the final findings may be awaited. Patients with lymph node metastases need radical inguinal lymph adenectomy.

Dynamic Sentinel Node Biopsy:

Dynamic sentinel node biopsy can be performed as an alternative to modified inguinal lymphadenectomy in patients with no evidence of adenopathy to reduce morbidity. he current technical standard of dynamic sentinel node biopsy is intraoperative detection using a gamma probe, preceded by an injection of a radioactive colloid marker around the tumor. The false-negative detection rate in modern high-volume series is around 7% (Leijte et al., 2009). If, on one side, no sentinel lymph node is detectable, a modified inguinal lymph node dissection is recommended. Patients with lymph node metastases need radical inguinal lymph adenectomy. See section inguinal lymphadenectomy for surgical technique and complications.

Radical Lymphadenectomy:

If lymph node metastases are detected in the above-mentioned modified or limited procedures, radical dissection of the ipsilateral inguinal lymph nodes is necessary; see section inguinal lymphadenectomy for surgical technique and complications. If two or more inguinal lymph node metastases or extranodal capsular tumor growth are found, ipsilateral removal of the iliac lymph nodes is recommended for complete staging. Furthermore, there is an indication for iliac lymphadenectomy in case of tumor recurrence in the groin during follow-up.

Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy for lymph node metastases:

Neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy appears beneficial in advanced tumor stages (N2–3). Current regimens use combinations of cisplatin, 5FU, and taxanes. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is used for primary unresectable fixed lymph node metastases (bulky disease) (Aziz et al., 2018) (Azizi et al., 2020).

Radiation Therapy of Lymph Node Metastases:

Adjuvant radiation therapy for proven lymph node metastases or radiation therapy of clinically suspicious lymph nodes before or instead of surgical treatment is not recommended outside of clinical trials. An established indication for radiotherapy exists in the palliation of fixed and ulcerated lymph node metastases if surgery and neoadjuvant chemotherapy are not feasible.

Chemotherapy of Advanced Penile Cancer

Due to the small case numbers of advanced penile carcinoma in developed countries, no prospective randomized trials for the below-mentioned treatment recommendations exist. Current regimens use combinations of cisplatin and taxanes. Median survival is around nine months; risk factors for poor prognosis include visceral metastases and poor performance status (Pond et al., 2014). While immunotherapies using checkpoint inhibitors are established for the treatment of SCC in other locations, no studies are available in patients with SCC of the penis. Individual case reports suggest a good response in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic penile SCC (Steck et al., 2021).

Paclitaxel and Cisplatin:

Cycle length of 21 days, four cycles are given for (neo)adjuvant indication (Noronha et al, 2012).

- Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 day 1

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 day 1

Paclitaxel, Cisplatin and 5-FU (Nicolai et al., 2015)

- Paclitaxel 120 mg/m2 day 1

- Cisplatin 75 mg/m2 day 1

- 5-Fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2 day 1–5

Paclitaxel, Cisplatin and Ifosfamide (Pagliaro et al., 2010)

- Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 day 1

- Cisplatin 25 mg/m2 days 1–3

- Ifosfamid 1200 mg/m2 days 1–3

Palliative Treatment of Penile Cancer

- Pain: see section pain medication for dosage of pain medication; consider palliative irradiation of painful lesions.

- Bleeding: the arrosion of the femoral vessels can cause pronounced and lethal bleeding. Palliative sedation should be discussed with the patient and prepared. Dark sheets should be ready to cover the bleeding.

- Odor: malignant ulcerative wounds cause a strong odor. Local antiseptics and systemically administered antibiotics such as clindamycin are helpful in addition to aromatics.

- Malignant lymphedema: helpful are skin care, palliative lymphatic drainage, possibly combined with percutaneous needle fluid drainage through small drainage bags (Pottharst et al., 2009).

Follow-up Care

Regular clinical examination of the penis (after partial penectomy) and inguinal lymph nodes can reliably detect recurrence. Assessments should be performed every three months for the first two years, after which biannual checks are sufficient. In addition, sonography (penis, inguinal lymph nodes, liver) and computed tomography (abdomen, pelvis, groin) are used, especially after therapy of lymph node metastases or invasive high-grade carcinoma. The evidence regarding imaging in follow-up is poor. The tumor marker SCC may be helpful for follow-up if elevated in advanced tumor disease. Recurrence in the inguinal lymph nodes can be expected within the first two years. Local recurrence may also occur many years after partial penectomy.

Prognosis of Penile Cancer

- Prognostic factors: the absence, presence, location, and number of lymph node metastases are important prognostic factors. The risk of lymph node metastases in T2 tumors is around 50%. Further important risk factors for prognosis are grading and vascular invasion.

- pN0: five-year survival rate (5-YSR) is 80% to 95%.

- pN+ inguinal: the number of lymph node metastases is relevant for prognosis, 67% 5-YSR with one or two lymph node metastases vs. 39% 5-YSR with more pronounced lymph node involvement.

- pN+ iliacal: 33% 5-YSR.

| Bowen disease | Index | Verrucous carcinoma of the penis |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

O. R. Brouwer, S. T. Tagawa, M. Albersen, B. Ayres, and C. Protzel, “EAU Guidelines: Penile Cancer.” Accessed: 2023. [Online]. Available: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/penile-cancer/

DGU, DKG, AWMF, and L. Onkologie, “S3-Leitlinie Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Peniskarzinoms.” Accessed: Aug. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/peniskarzinom/

M. Azizi et al., “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis-Is there a Benefit in Using Neoadjuvant Systemic Chemotherapy for Locally Advanced Penile Squamous Cell Carcinoma?,” J Urol, p. 101097JU0000000000000746, 2020.

Catalona 1988 CATALONA, W. J.:

Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with

preservation of saphenous veins: technique and preliminary results.

In: J Urol

140 (1988), Nr. 2, S. 306–10

Colberg, C.; van der Horst, C.; Jünemann, K.-P. &

Naumann, C. M.

[Epidemiology of penile cancer].

Der Urologe, 2018,

57, 408-412

J. Crook, “Contemporary Role of Radiotherapy in the Management of Primary Penile Tumors and Metastatic Disease.,” Urol Clin North Am., vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 435–448, 2016.

Culkin und Beer 2003 CULKIN, D. J. ; BEER,

T. M.:

Advanced penile carcinoma.

In: J Urol

170 (2003), Nr. 2 Pt 1, S. 359–65

Doehn u.a. 2001 DOEHN, C. ; BAUMGARTEL, M. ;

JOCHAM, D.:

[Surgical therapy of penis carcinoma].

In: Urologe A

40 (2001), Nr. 4, S. 303–7

Erbersdobler, A.

[Pathology and

histopathological evaluation of penile cancer].

Der Urologe, 2018,

57, 391-397

Gerber 1994 GERBER, G. S.:

Carcinoma in situ of the penis.

In: J Urol

151 (1994), Nr. 4, S. 829–33

Haas u.a. 1999 HAAS, G. P. ; BLUMENSTEIN,

B. A. ; GAGLIANO, R. G. ; RUSSELL, C. A. ; RIVKIN,

S. E. ; CULKIN, D. J. ; WOLF, M. ; CRAWFORD,

E. D.:

Cisplatin, methotrexate and bleomycin for the treatment of carcinoma

of the penis: a Southwest Oncology Group study.

In: J Urol

161 (1999), Nr. 6, S. 1823–5

Höpfl u.a. 2001 HÖPFL, R. ; GUGER, M. ;

WIDSCHWENDTER, A.:

Humane Papillomviren und ihre Bedeutung in der Karzinogenese.

In: Hautarzt

52 (2001), S. 834–846

Kroon u.a. 2005 KROON, B. K. ; HORENBLAS, S. ;

NIEWEG, O. E.:

Contemporary management of penile squamous cell carcinoma.

In: J Surg Oncol

89 (2005), Nr. 1, S. 43–50

Nicolai, N.; Sangalli, L. M.; Necchi, A.; Giannatempo,

P.; Paganoni, A. M.; Colecchia, M.; Piva, L.; Catanzaro, M. A.; Biasoni,

D.; Stagni, S.; Torelli, T.; Raggi, D.; Faré, E.; Pizzocaro, G. &

Salvioni, R.

A Combination of Cisplatin and 5-Fluorouracil With a

Taxane in Patients Who Underwent Lymph Node Dissection for Nodal

Metastases From Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Penis: Treatment Outcome

and Survival Analyses in Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Settings.

Clin

Genitourin Cancer, 2015

Noronha, V.; Patil, V.; Ostwal, V.; Tongaonkar, H.;

Bakshi, G. & Prabhash, K.

Role of paclitaxel and platinum-based

adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk penile cancer.

Urol Ann, 2012,

4, 150-153

G. R. Pond et al., “Prognostic risk stratification derived from individual patient level data for men with advanced penile squamous cell carcinoma receiving first-line systemic therapy.,” Urologic oncology, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 501–508, 2014.

Shammas, F. V.; Ous, S. & Fossa, S. D.

Cisplatin

and 5-fluorouracil in advanced cancer of the penis.

J Urol, 1992,

147, 630-632.

S. Steck, W. Went, and D. Kienle, “Profound and durable responses with PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with metastatic penile squamous cell carcinoma,” Curr Probl Cancer, 2021.

Deutsche Version: Ursachen und TNM Tumorstadien des Peniskarzinoms

Deutsche Version: Ursachen und TNM Tumorstadien des Peniskarzinoms