You are here: Urology Textbook > Penis > Posterior urethral valves

Diagnosis and Treatment of Posterior Urethral Valves

Definition

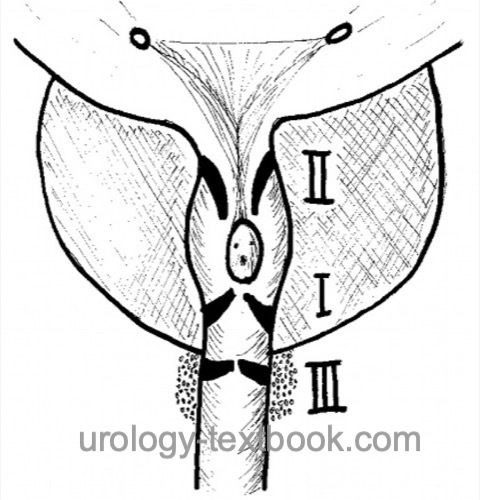

Posterior urethral valves (PUV) are remnants of embryonic development in the prostatic or membranous urethra causing congenital lower urinary tract obstruction (CLUTO). PUV may cause significant long-term dysfunction of the lower and upper urinary tract. Posterior urethral valves are classified by Young [fig. Classification of PUV]:

- Type I (90–95%): slit-like membrane arising from the verumontanum and fused anterior and connected to the membranous urethra proximal to the external sphincter.

- Type II: a fold of superficial muscle fibers that run from the verumontanum to the bladder neck and are considered non-obstructive.

- Type III: an annular membrane in the membranous urethra anterior to the verumontanum. It results from the lack of resolution of the urogenital membrane and causes severe obstruction.

|

Review literature: (Agarwal, 1999) (Carr and Snyder, 2004) (Glassberg, 2001). EAU guidelines: Paediatric Urology.

Epidemiology

Posterior urethral valves are the most common cause of fetal lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO): 1–2/10000 male births.

Pathophysiology of Posterior Urethral Valves

Congenital urinary valves induce secondary damage to the urinary tract, which persists even after successful therapy.

Glomerular filtration:

Chronic hydronephrosis results in impaired renal development with microcystic renal dysplasia. Recurrent urinary tract infections, vesicoureteral reflux, and persistent hydronephrosis after therapy result in subsequent damage to the kidney. In the course of the disease, end-stage renal disease may develop due to increasing body weight with a higher workload for the kidneys.

Renal tubular function:

The renal development under high intraluminal pressure causes damage to the distal nephron and impaired renal concentrating capacity. The children are vulnerable to fluid loss (fever, diarrhea, or vomiting).

Chronic hydronephrosis:

Despite therapy of subvesical obstruction, not all children rapidly attain improvement in dilatation of the upper urinary tract. High urine flow due to tubular dysfunction is one cause of chronic dilatation. In addition, massively dilated ureters may be obstructive due to inadequate peristalsis and ureteral kinking. However, ureteral reconstruction is rarely necessary after urodynamic testing (Whitaker test).

Vesicoureteral Reflux (VUR):

30–50% of children with posterior urethral valves show unilateral or bilateral VUR. Unilateral and bilateral VUR is a risk factor for end-stage renal failure. Unilateral reflux was thought to be protective for the contralateral kidney by serving as a pressure valve, thereby reducing the risk for end-stage renal failure (posterior urethral Valves, Unilateral vesicoureteral Reflux, and renal Dysplasia = VURD syndrome). Long-term studies failed to prove a protective effect. After relief of subvesical obstruction, spontaneous healing of VUR is expected in 30%.

Valve bladder syndrome:

The following mechanisms may contribute to significant bladder dysfunction: thickened bladder wall with increased collagen content, decreased bladder compliance, autonomic detrusor contractions with incontinence and increased micturition pressures, polyuria due to renal insufficiency, and decreased urinary bladder sensitivity. During childhood development, urinary bladder emptying decompensates with postvoid residuals. Valve bladder syndrome is a risk factor for renal failure and also jeopardizes the success of renal transplantation.

Signs and Symptoms

The symptoms and prognosis of posterior urethral valves depend on the age at presentation.

Antenatal symptoms:

Oligohydramnios, hydronephrosis, and megacystis are signs of CLUTO (congenital lower urinary tract obstruction): most commonly caused by posterior urethral valves, but also other urethral malformations, Prune-Belly syndrome or severe vesicoureteral reflux.

Symptoms of Newborns:

Abdominal tumor, urinary ascites due to fornix rupture, respiratory distress due to pulmonary hypoplasia. History of oligohydramnios. Up to 25% terminal renal failure. Clinically relevant pulmonary hypoplasia causes 50% mortality.

Infancy to school-age children:

Recurrent urinary tract infections, weak urinary stream, voiding symptoms, microhematuria, incontinence, and enuresis nocturna. Up to 10% of the children develop terminal renal failure until puberty.

Diagnosis of Posterior Urethral Valves

Laboratory tests:

Creatinine, electrolytes, and blood gas tests guide initial treatment decisions in perinatal manifestations. Elevated creatinine and proteinuria during follow-up are predictive of future renal failure.

Ultrasound imaging:

Evaluation of the upper urinary tract: hydronephrosis? Parenchymal thickness? Evaluation of the lower urinary tract [fig. bladder ultrasound imaging]: bladder wall thickness? Dilatation of the prostatic urethra? Megaureter? Residual urine?

|

Voiding cystourethrography:

Imaging technique for definitive diagnosis, after inserting a small feeding tube into the bladder or using a suprapubic catheter [fig. VCUG in PUV (schema) and VCUG in PUV]. Voiding cystourethrography is performed in oblique projection (one side of the pelvis elevated) to obtain a good view of the posterior urethra.

|

|

Renal scintigraphy:

Renal scintigraphy is indicated for persistent hydronephrosis after therapy for subvesical obstruction to detect significant upper urinary tract obstruction. GFR measured during renal scintigraphy is a critical prognostic parameter for future renal failure. A glomerular filtration rate below 70 ml/min/1.73 m2 at one year of age is prognostically unfavorable.

Urodynamics:

Urodynamic testing is needed when bladder function deteriorates during childhood (residual urine, incontinence, VUR).

Cystoscopy:

Cystoscopy is done if the child is fit for anesthesia, in combination with endoscopic valve ablation.

Treatment of Posterior Urethral Valves

Prenatal therapy:

The prenatal placement of a vesicoamniotic shunt can ensure bladder drainage for improved genitourinary organ development. Randomized trials have failed to demonstrate renal or pulmonary improvement compared with prompt and sufficient postpartum therapy (Morris et al., 2013). Problematic is the difficulty of a correct prenatal diagnosis (DD urethra atresia, prune-belly syndrome, VUR, multicystic dysplastic kidney) and the potential complications of the intervention. Therapy involves risks to the mother (infection, bleeding) and the fetus (hemorrhage, infection, adjacent organ injury, preterm labor, premature closure of the vesicoamniotic shunt). The best secured indication for prenatal therapy is a fetus with subvesical obstruction (megacystis) and bilateral hydronephrosis with initial normal amniotic fluid, who develops oligohydramnios during follow-up. Experimental new techniques include fetal cystoscopy with laser treatment of the urethral valves.

Initial therapy of perinatal manifestation:

The initial goal is to drain the urinary bladder. Usually, thin (6 CH) non-blockable catheters are used (feeding tube, short DJ stent); these are placed transurethrally or suprapubically percutaneously, depending on the bladder volume and clinical situation. Other therapeutic goals are correcting electrolyte disturbances and treating respiratory insufficiency due to pulmonary hypoplasia.

Vesicostomy:

In children too small or too sick for endoscopic valve ablation, an open surgical vesicostomy is done for efficient drainage of the bladder. The urachus is exposed via a small incision between the umbilicus and symphysis, which allows the bladder dome to be pulled out to the level of the abdominal wall and create a stoma.

Endoscopic valve ablation:

In stabilized neonates (fit for anesthesia), radiological imaging (VCUG) and endoscopic ablation of the urethral valve (TURPUV) are performed (at 12 o'clock, 4 o'clock, and 8 o'clock positions using a cold knife or laser). Crucial to avoiding urethral stricture is the use of thin instruments and avoidance of monopolar cautery.

Circumcision:

Prophylactic circumcision at the time of endoscopic valve ablation significantly (3% vs. 20%) reduces the risk of febrile urinary tract infections later during follow-up, especially in boys with reflux or nonretractile foreskin (Harper et al., 2022).

Follow-up care after endoscopic valve ablation:

Regular ultrasound imaging of postvoid residual volume and hydronephrosis. Regular blood sampling to monitor renal function. In case of insufficient bladder emptying and persistent hydronephrosis, repeat radiological imaging is necessary (VCUG, cystoscopy, renal scintigraphy), possibly also urodynamics, depending on the child's age.

Therapy of persistent hydronephrosis:

Temporary upper urinary diversion is used to treat persistent hydronephrosis after sufficient bladder drainage and insufficient stabilization of kidney function. However, long-term studies have shown no improvement in prognosis concerning renal failure, and other disadvantages include the deterioration of bladder capacity and complex reoperation (Smith et al., 1996) (Chua et al., 2018). However, temporary urinary diversion of the upper tract may rarely be necessary for renal failure with worsening hydronephrosis or sepsis with an infected upper urinary tract. Possible techniques include distal ureterostomy, proximal loop ureterostomy, ring ureterostomy, or pyelostomy.

Treatment of the valve bladder syndrome:

Regular bladder emptying (toilet training, nocturnal micturition) is a primary measure. Depending on urodynamics and postvoid residual volume, alpha-blockers, intermittent catheterization, and anticholinergics may be prescribed. If treatment fails, overnight catheter drainage via transurethral catheter or catheterizable bladder stoma (Mitrofanoff appendicovesicostomy) is an option (Nguyen et al., 2005).

Therapy of vesicoureteral reflux:

Please see section vesicoureteral reflux for the principles of VUR treatment. Long-term antibiotics (chemoprophylaxis) are started for recurrent urinary tract infections. Therapy of the valve bladder syndrome helps to reduce micturition pressures. Ureteral reimplantation is associated with more complications due to the thick bladder wall and should be avoided if possible.

Prognosis of PUV

In historical publications, the mortality up to puberty was 50%; modern therapeutic methods and the availability of renal transplantation have drastically improved this.

Time of diagnosis:

The earlier the urethral valve becomes symptomatic, the more pronounced the clinical picture usually is and the worse the prognosis. If the disease is symptomatic within the first two months of life, the mortality within one year is 10%; when diagnosed later in the first year, the mortality is 1%.

Creatinine and GFR:

For patients with perinatal manifestation, creatinine nadir after bladder drainage of >1.4 mg/dl is prognostically unfavorable for future renal function. After the first year of life, renal function has a good prognosis if the creatinine concentration is <1 mg/dl or the GFR is above 70 ml/min/1.73 m2. Worse values are at increased risk for end-stage renal failure in pubertal age. End-stage renal disease may also develop in up to 10% of patients with late clinical presentation (over five years).

| Hypospadias | Index | Meatal stenosis |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Agarwal 1999 AGARWAL, S.:

Urethral valves.

In: BJU Int

84 (1999), Nr. 5, S. 570–8

Carr und Snyder 2004 CARR, M. C. ; SNYDER,

H. M.:

[Urethral valves. Fate of the bladder and upper urinary tract].

In: Urologe A

43 (2004), Nr. 4, S. 408–13

Glassberg 2001 GLASSBERG, K. I.:

The valve bladder syndrome: 20 years later.

In: J Urol

166 (2001), Nr. 4, S. 1406–14

Young u.a. 1919 YOUNG, H. H. ; FRONTZ, W. A. ;

BALDWIN, J. C.:

Congenital obstruction of the posterior urethra.

In: J Urol

3 (1919), S. 289

Deutsche Version: Diagnose und Therapie von hinteren Harnröhrenklappen

Deutsche Version: Diagnose und Therapie von hinteren Harnröhrenklappen

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.