You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > Prostate biopsy

Transrectal and Perineal Prostate Biopsy: Technique and Complications

Indications for Prostate Biopsy

Prostate biopsy is indicated in cases of suspected prostate cancer:

- Increased or rising PSA concentration

- Suspicious digital-rectal examination

- Suspicious imaging of the prostate gland

Contraindications of Prostate Biopsy

Urinary tract infection, prostatitis, absent rectum, contraindications for lithotomy position, coagulation disorders, and severe comorbidity speaking against an elective scheduled procedure.

Technique of Prostate Biopsy

Patient Preparation

- Exclude or treat urinary tract infections

- Reduce the bacterial load in the rectum with a povidone-iodine suppository before transrectal biopsy.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis

See also section perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis. The standard recommendation has been oral long-acting fluoroquinolone for 1--3 days, e.g., ciprofloxacin 500 mg 1-0-1. Because of potentially serious side effects, fluoroquinolones have lost approval for prophylactic use (DSM, 2019). Alternative antibiotics are aminopenicillins, fosfomycin, gentamicin or cephalosporins, some of which are combined. A current standard does not exist. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not mandatory for perineal prostate biopsy.

Anesthesia for Prostate Biopsy

Periprostatic infiltration anesthesia with local anesthetic, preferably in combination with a diclofenac suppository. 20 ml of local anesthetic is infiltrated on both sides of the prostate in the region of the neurovascular bundles before the biopsy. Additional infiltration of the skin and needle path through the pelvic floor is necessary for transperineal biopsy. Spinal or general anesthesia is helpful for pain-sensitive patients or prostate saturation biopsy.

Sampling Technique:

Perform prostate biopsy with either a transrectal or transperineal technique. Use an 18G true cut biopsy needle under transrectal ultrasound guidance to gain the prostate cores.

Numbers and locations of the prostate cores:

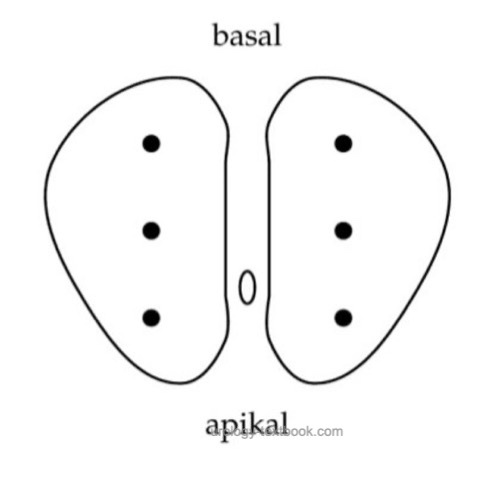

The minimum of prostate samples is six cores (sextant biopsy), three from each prostate lobe (apical, middle, and basal) [fig. sextant prostate biopsy] (Hodge et al., 1989). The EAU guideline recommends at least ten biopsy cores. Add additional cores from suspicious (hypoechoic) lesions of the prostate. Send the prostate cores separately to the pathologist to get information on the prostate cancer tumor volume for, e.g., nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

|

Sextant prostate biopsy can detect more cancer, if biopsy targets the prostate near the prostate capsule (Stamey, 1995). The biopsy needle advances 2 cm into the tissue; this must be anticipated before biopsy. Especially apical biopsies can injure the dorsal venous plexus of the prostate.

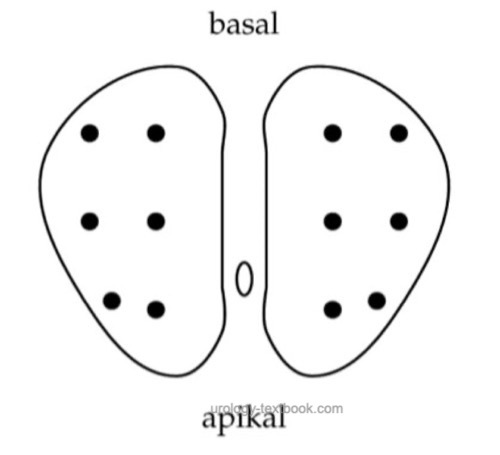

Prospective studies demonstrated an improved sensitivity by increasing the prostate core number. Obtain the additional sampling from near the prostate organ capsule and the transitional zone [fig. increased sampling in prostate biopsy]. Not all randomized trials have demonstrated this effect. Additionally, increased sampling may detect more clinically insignificant prostate cancers. 80% of prostate cancers are diagnosed with the first prostate biopsy, 10% with the second prostate biopsy, 7% with the third prostate biopsy, and 3% with the fourth prostate biopsy.

|

MRI/Ultrasound Fusion Guided Prostate Biopsy:

Multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) is performed to localize suspicious lesions in the prostate; see also section screening of prostate cancer. Targeting prostate biopsy to the suspicious areas is possible with MR-guided in-bore biopsy or with MRI-ultrasound fusion (hardware fusion or cognitive fusion). No significant advantages were found in the prospective studies comparing different targeting techniques.

- MRI targeted biopsy: the in-bore MRI biopsy is performed during the MRI examination. The technique is very complex and expensive and is rarely performed.

- MRI-ultrasound fusion biopsy: special hardware and software are used to present the image data of the mpMRI during ultrasound imaging. The software and hardware for fusion biopsy are still very expensive.

- Cognitive fusion biopsy: a cost-effective method that requires good spatial orientation in the prostate during transrectal sonography. The suspicious MRI lesions are linked in thought with the image of the transrectal sonography, and thus, a targeted biopsy is performed.

Complications of Prostate Biopsy

Mild complications are relatively common (over 50%), and serious complications are uncommon (Rodriguez and Terris, 1998).

Infections after prostate biopsy:

Urinary tract infections, bacterial prostatitis. Rarely urosepsis (1% for transrectal biopsy), which may be fatal. The risk for infectious complications is increasing due to rising antibiotic resistance (Loeb et al., 2012).

Bleeding:

50% of patients have minor hematuria for up to seven days. Hematospermia in 30%, this can last up to a month. Heavy rectal bleeding requires tamponade.

Other complications of prostate biopsy:

- Urinary retention (1–2%)

- Vasovagal reaction (5%)

- Adverse reactions from the local anesthetic, such as dizziness, nausea, syncope, cardiac arrhythmias or seizures.

| Urinary diversion | Index | TURP |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Arzneikommission der deutschen Ä rzteschaft, “Drug Safety Mail 2019-40: Information zu Fluorchinolonen: Prophylaktische Anwendung im Zuge urologischer Eingriffe,” 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.akdae.de/Arzneimittelsicherheit/DSM/Archiv/2019-40.html.Hodge u.a. 1989 HODGE, K. K. ; MCNEAL, J. E. ; TERRIS, M. K. ; STAMEY, T. A.: Random systematic versus directed ultrasound guided transrectal core biopsies of the prostate.

In: J Urol

142 (1989), Nr. 1, S. 71–4; discussion 74–5

Lee, D. J.; Recabal, P.; Sjoberg, D. D.; Thong, A.; Lee, J. K.; Eastham, J. A.; Scardino, P. T.; Vargas, H. A.; Coleman, J. & Ehdaie, B. Comparative Effectiveness of Targeted Prostate Biopsy Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging Ultrasound Fusion Software and Visual Targeting: a Prospective Study.

The Journal of urology, 2016, 196, 697-702.

Loeb, S.; van den Heuvel, S.; Zhu, X.; Bangma, C. H.;

Schröder, F. H. & Roobol, M. J.

Infectious complications and

hospital admissions after prostate biopsy in a European randomized trial.

Eur. Urol. 2012,

61, 1110-1114.

Puech, P.; Rouvière, O.; Renard-Penna, R.;

Villers, A.; Devos, P.; Colombel, M.; Bitker, M.-O.; Leroy, X.;

Mège-Lechevallier, F.; Comperat, E.; Ouzzane, A. & Lemaitre, L.

Prostate

cancer diagnosis: multiparametric MR-targeted biopsy with cognitive and

transrectal US-MR fusion guidance versus systematic biopsy--prospective

multicenter study.

Radiology, 2013, 268, 461-469.

Rodriguez und Terris 1998 RODRIGUEZ, L. V. ;

TERRIS, M. K.:

Risks and complications of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate

needle biopsy: a prospective study and review of the literature.

In: J Urol

160 (1998), Nr. 6 Pt 1, S. 2115–20

Stamey 1995 STAMEY, T. A.:

Making the most out of six systematic sextant biopsies.

In: Urology

45 (1995), Nr. 1, S. 2–12

Wegelin, O.; Exterkate, L.; van der Leest, M.;

Kummer, J. A.; Vreuls, W.; de Bruin, P. C.; Bosch, J. L. H. R.; Barentsz,

J. O.; Somford, D. M. & van Melick, H. H. E.

The FUTURE Trial: A

Multicenter Randomised Controlled Trial on Target Biopsy Techniques Based

on Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer in

Patients with Prior Negative Biopsies.

European urology, 2019,

75, 582-590.

Wysock, J. S.; Rosenkrantz, A. B.; Huang, W. C.;

Stifelman, M. D.; Lepor, H.; Deng, F.-M.; Melamed, J. & Taneja, S. S.

A

prospective, blinded comparison of magnetic resonance (MR)

imaging-ultrasound fusion and visual estimation in the performance of

MR-targeted prostate biopsy: the PROFUS trial.

European urology, 2014,

66, 343-351.

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der transrektalen und transperinealen (Fusions-) Prostatabiopsie

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der transrektalen und transperinealen (Fusions-) Prostatabiopsie

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.