You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > Cystectomy

Radikale Zystektomie: Surgical Technique (Step-by-Step) and Complications

Indications for Cystectomy

Radical Cystectomy:

Radical cystectomy is the resection of the urinary bladder with a safety margin and pelvic lymphadenectomy. In addition, the prostate is also removed in men. In women, a segment of the anterior vaginal wall, uterus, and optionally the ovaries are removed. Indications for radical cystectomy are:

- Muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma without distant metastases

- Superficial high-grade urinary bladder carcinoma with a high risk of progression in young patients (early elective cystectomy)

- Recurrent superficial high-grade bladder carcinoma

- Endoscopically uncontrollable superficial bladder carcinoma

- Palliative cystectomy for advanced bladder carcinoma and refractory bleeding, fistulae, or lack of bladder capacity with pollakiuria

Simple Cystectomy:

Simple cystectomy is the resection of the urinary bladder without a safety margin and without pelvic lymphadenectomy. In men, comparable to simple prostatectomy, the prostatic capsule is left in situ to improve continence and potency after orthotopic urinary diversion. In women, the internal genital organs are spared. Indications for simple cystectomy are:

- Lack of bladder capacity after radiotherapy, urogenital tuberculosis, schistosomiasis, or interstitial cystitis.

Contraindications of Cystectomy

Untreated coagulation disorders. The other contraindications depend on the surgical risk due to the patient's comorbidity, and the surgical procedure's impact on the patient's life expectancy and quality of life.

Step-by-Step Surgical Technique of Cystectomy

Preoperative patient preparation:

- Stoma counseling and preoperative stoma site marking, even if orthotopic neobladder is anticipated.

- Exclude or treat urinary tract infections.

- Bowel preparation depends on the planned urinary diversion

- Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis: cephalosporin combined with metronidazole, alternatively gentamicin combined with metronidazole or aminopenicillin with penicillinase inhibitor combined with metronidazole.

- Anesthesia: the combination of an epidural with general anesthesia lowers intraoperative and postoperative opiate requirements, reduces intraoperative bleeding, and accelerates postoperative gastrointestinal recovery (Ozyuvaci et al., 2005).

- Perioperative gastric tube.

- Patient positioning: supine position with slight hyperextension of the lumbar spine and slight abduction of the legs. Skin disinfection from nipples to midthighs. Draping with access to the external genitals, insert a 22 CH catheter with 30 ml balloon inflation.

Surgical Approach for Cystectomy

Lower midline laparotomy from symphysis to umbilicus, if necessary extend the incision to the left of the umbilicus. The retropubic space is developed bluntly. Open the peritoneal cavity near the umbilicus, expose the urachus, and divide between ligatures. The peritoneum is incised on both sides of the urinary bladder. Examine the abdominal cavity for metastases. Incise the right white line of Toldt and continue with the incision around the caecum for complete mobilization of the right colon. Identify the right ureter. Incise the left white line of Toldt to mobilize the sigmoid colon. Identify the left ureter. For good exposure of the pelvic cavity, the bowel is packed into the upper abdomen with moist and warm laparotomy towels and using a retraction system.

Cystectomy in Male Patients

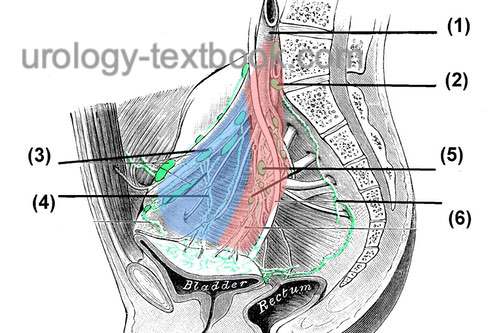

Pelvic lymphadenectomy:

Incise the parietal peritoneum along the external iliac artery and transect the deferent ducts. Perform pelvic lymphadenectomy on both sides: the dissection borders for standard lymphadenectomy are laterally the genitofemoral nerve, caudally the superior ramus of the os pubis, medially the umbilical ligament and the urinary bladder, dorsally the obturator nerve and the pelvic diaphragm, cranially the ureter and the bifurcation of the common iliac artery [fig. pelvic lymphadenectomy]. The iliac vessels are freed from the surrounding lymphatic tissue circularly. During this procedure, divide and ligate the first branches from the internal iliac artery (superior vesical artery and the umbilical artery). A careful dissection technique with bipolar coagulation, application of clips, and thin ligatures reduces the complication rate due to lymphoceles.

|

For extended lymphadenectomy, remove the lymphatic tissue along the vasa iliaca communis to the aorta. Data from retrospective studies speculated better tumor-free survival by extended lymphadenectomy, but statistical flaws (Will Rogers phenomenon) make evaluation difficult. In two prospective randomized studies, extended lymphadenectomy did not improve survival (Gschwend et al., 2019a).

Dissection of the ureters:

Transect the ureters near the bladder and send the distal portion for frozen sectioning examination. The ureters are splinted with MJ ureteral stents (secured with 4-0 fast absorbing sutures), which allows for the atraumatic management of the ureters during the next steps. Dissect the ureters as little as possible to maintain their blood supply (caution: ureteral stricture).

Division of the bladder pedicles:

Incise the peritoneal fold between the bladder and the rectum at the deepest point across its entire width, and develop the layer between the rectum and the bladder bluntly in the midline. Use the left hand to pull the urinary bladder anteriorly and caudally, and the bladder pedicles with the vascular supply will become visible. Grasp the bladder pedicle between the index finger and middle finger. Step by step, the right and left bladder pedicles are divided between clips, ligatures, GIA, or vascular sealing devices. For a nerve-sparing cystectomy, the line of dissection must be close to the urinary bladder. Both seminal vesicles are exposed after transection of Denonvillier's fascia, and the layer between the rectum and prostate is bluntly developed.

Ascending dissection of the prostate:

Retract the prostate (and urinary bladder) in a dorso-cranial direction. Clear the ventral prostate from fatty tissue, and divide interfering superficial veins after coagulation or clipping. Incise the endopelvic fascia and puboprostatic ligaments on both sides. Bluntly expose the apex of the prostate with a dissecting swab.

Division of the dorsal vein complex:

Grasp the dorsal vein complex over the prostate apex with a Babcock clamp and secure the venous plexus with suture ligation. Gradually transect the venous plexus until reaching the urethra. Significant bleeding vessels are coagulated or sutured.

Nerve-sparing:

Incise the fascia overlying the prostate and sweep the cavernosal nerves to the lateral. Use an overholt clamp for dissection and clips to stop bleeding from small vessels. Separate the urethra from the cavernous nerve bundle with a right-angle clamp and pass a strong ligature (USP 1–2) around the urethra. Tie the ligature close to the prostate apex to avoid tumor cell seeding after transection.

Division of the urethra:

Divide the ventral hemicircumference of the urethra distal to the ligature until the catheter is visible. Consider a frozen section examination of the urethra. At 9, 11, 1, and 3 o'clock, anastomotic sutures are placed if orthotopic urinary diversion is anticipated (double-armored sutures such as PDS 2-0 or Vicryl 2-0 with 5/8 needle).

Clamp and divide the foley catheter in the opened urethra and dispose of the valve piece. The clamped catheter serves as a mobilization aid for further dissection. Dissect the dorsal urethra and rectourethral muscle. Place two anastomotic sutures at the 5 and 7 o'clock position of the urethra. The dorsal anastomotic sutures may additionally be passed through the dorsal external sphincter complex (or place additional sutures) to improve early continence and tightness of the anastomosis (Rocco et al., 2009).

Dissection of the prostate:

The layer between the rectum and the prostate is now visualized by dissecting remnants of the external sphincter muscle and by blunt finger dissection. Separate the cavernous nerve from the prostate with overholt dissection and transect vessels to the prostate between clips.

Dissection of seminal vesicles:

Continue with the ascending dissection of the prostate until the seminal vesicles are visible. Dissect vessels to the seminal vesicles between clips. Staying close to the seminal vesicles and urinary bladder is essential if you intend nerve-sparing. Avoid urine spilling during dissection and removal of the specimen. Careful irrigation and hemostasis are paramount after cystectomy. Use thin figure-of-eight sutures for remaining bleeders and pack the pelvic cavity during the urinary diversion procedure.

Urinary diversion:

Please see the section on urinary diversion for the different options.

Cystectomy in Female Patients

See the section above for preoperative patient preparation, antibiotic prophylaxis, patient positioning, and surgical access.

Pelvic lymphadenectomy and dissection of the ureters:

The dissection of the ligament teres uteri enables access to the region of the pelvic lymphadenectomy. In young women, the ovaries are spared. The surgical technique of pelvic lymphadenectomy and dissection of the ureters is comparable to that of male patients; see the previous section.

Division of the bladder pedicles:

Incise the peritoneal fold between the uterus and the rectum at the deepest point across its entire width, and bluntly develop the layer between the rectum and the vagina in the midline. Use the left hand to pull the bladder and uterus anteriorly and caudally; the bladder pedicles with the vascular supply will become visible. Grasp the bladder pedicle between the index finger and middle finger. Step by step, the right and left bladder pedicles are divided between clips, ligatures, GIA, or vascular sealing devices. For a nerve-sparing cystectomy, the line of dissection must be close to the urinary bladder. Transect the cardinal ligament with the vascular supply to the uterus, and the lateral vaginal wall can be visualized. A sponge-stick soaked with povidone-iodine in the vagina helps to identify the posterior fornix, where the vagina is opened transversely. The opening of the vagina is extended toward the urethra close to the anterior midline.

Vagina-sparing cystectomy:

Vagina-sparing cystectomy is possible in selected patients: absence of tumor at the bladder neck or urethra and no sign of infiltration of the anterior vaginal wall and parametria. A circumferential incision is made around the cervix. The bladder is dissected from the anterior vaginal wall with descending and ascending technique after division of the urethra.

Uterus-sparing cystectomy:

Uterus-sparing cystectomy is possible in selected patients: absence of tumor at the bladder neck or urethra and no sign of infiltration of the anterior vaginal wall and parametria. Cystectomy starts with the incision of the peritoneal fold between the bladder and uterus. The division of the bladder pedicles must spare the uterine vessels. The bladder is dissected from the anterior vaginal wall with a descending and ascending technique after division of the urethra.

Dissection of the urethra:

Retract the specimen in a dorso-cranial direction. Clear the ventral bladder surface from fatty tissue and divide interfering superficial veins after coagulation or clipping. Incise the endopelvic fascia and the pubovesical ligaments on both sides. Grasp the dorsal vein complex over the urethra with a Babcock clamp and secure the venous plexus with suture ligation. Gradually transect the venous plexus until reaching the urethra. Significant bleeding vessels are coagulated or sutured. The circumference of the urethra (between sphincter and bladder neck) is mobilized using a right-angle clamp. Pass a strong ligature (USP 1–2) around the urethra and tie it around the catheter at the bladder neck to prevent urine spillage during the next steps.

Urethrectomy with heterotopic urinary diversion:

Further urethral dissection is done with traction on the urethra, which is dissected up to the meatus. The circumference of the meatus is incised for complete mobilization of the urethra. The clamped catheter is pulled into the pelvis and serves as a mobilization aid with preserved balloon inflation. The perineum (urethral orifice) is closed after the specimen is removed.

Preservation of the urethra for orthotopic urinary diversion:

Divide the ventral hemicircumference of the urethra distal to the ligature until the catheter is visible. Consider a frozen section examination of the urethra. At 9, 11, 1, and 3 o'clock, anastomotic sutures are placed if orthotopic urinary diversion is anticipated (double-armored sutures such as PDS 2-0 or Vicryl 2-0 with 5/8 needle). Clamp and divide the bladder catheter in the opened urethra and dispose of the valve piece. The clamped catheter serves as a mobilization aid for further dissection. Transect the dorsal urethra and place two anastomotic sutures at the 5 and 7 o'clock position of the urethra. The dorsal anastomotic sutures may additionally be passed through the dorsal external sphincter complex (or place additional sutures) to improve early continence and tightness of the anastomosis (Rocco et al, 2009).

Final steps:

The final dissection steps include the resection of the anterior vaginal wall. If orthotopic urinary diversion is planned, little or none of the anterior vaginal wall should be removed because important nerves for the sphincter run along the anterior wall. Close the anterior vaginal wall with a single layer running suture in a transverse direction. Place an iodinated tamponade in the vagina for one day.

Urinary diversion:

Please see the section on urinary diversion for the different options.

Postoperative Care after Cystectomy

Please see section urinary diversion for the postoperative care.

Complications of Cystectomy

Complications occur in 25–35% of cases, and mortality is 1–3% (Chang et al., 2001) (Chang et al., 2002c). The postoperative complication rate is significantly influenced by age and existing comorbidities, which include cardiovascular disease, renal insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune disease, previous abdominal surgery, locally advanced tumor stages, and obesity. It is controversial whether minimally invasive surgical techniques can reduce complication rates. Mortality is comparable between open or robotic-assisted laparoscopic cystectomy (Johar et al., 2013).

- Cardiopulmonary complications: atelectasis, pneumonia, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, heart failure.

- Gastrointestinal complications: paralytic ileus, mechanical ileus, anastomotic insufficiency, peritonitis, intra-abdominal abscess, rectal injury with fistulization.

- Bleeding: postoperative bleeding, surgical revision, transfusions, hematomas.

- Other complications: Wound infection, erectile dysfunction, female sexual dysfunction such as dyspareunia, lymphocele, leg and genital edema due to impaired lymphatic drainage.

- Complications of urinary diversion: see next section

| Bladder diverticulectomy | Index | Principles of urinary diversion |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Chang u.a. 2002 CHANG, S. S. ; COOKSON, M. S. ; BAUMGARTNER, R. G. ; WELLS, N. ; SMITH, Jr.: Analysis of early complications after radical cystectomy: results of a collaborative care pathway.In: J Urol

167 (2002), Nr. 5, S. 2012–6

Chang u.a. 2001 CHANG, S. S. ; SMITH, Jr. ;

WELLS, N. ; PETERSON, M. ; KOVACH, B. ;

COOKSON, M. S.:

Estimated blood loss and transfusion requirements of radical

cystectomy.

In: J Urol

166 (2001), Nr. 6, S. 2151–4

DGU

S3-Leitlinie: Früherkennung, Diagnose, Therapie

und Nachsorge des Harnblasenkarzinoms. https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/harnblasenkarzinom

Gschwend, J. E.; Heck, M. M.; Lehmann, J.; Rübben,

H.; Albers, P.; Wolff, J. M.; Frohneberg, D.; de Geeter, P.; Heidenreich,

A.; Kälble, T.; Stöckle, M.; Schnöller, T.; Stenzl, A.; Müller, M.; Truss,

M.; Roth, S.; Liehr, U.-B.; Leißner, J.; Bregenzer, T. & Retz, M.

Extended

Versus Limited Lymph Node Dissection in Bladder Cancer Patients Undergoing

Radical Cystectomy: Survival Results from a Prospective, Randomized Trial.

European

urology, 2019, 75, 604-611.

Johar, R. S.; Hayn, M. H.; Stegemann, A. P.; Ahmed, K.;

Agarwal, P.; Balbay, M. D.; Hemal, A.; Kibel, A. S.; Muhletaler, F.;

Nepple, K.; Pattaras, J. G.; Peabody, J. O.; Palou Redorta, J.; Rha,

K.-H.; Richstone, L.; Saar, M.; Schanne, F.; Scherr, D. S.; Siemer, S.;

Stökle, M.; Weizer, A.; Wiklund, P.; Wilson, T.; Woods, M.; Yuh, B. &

Guru, K. A.

Complications after robot-assisted radical cystectomy:

results from the International Robotic Cystectomy Consortium.

Eur

Urol, 2013, 64, 52-57.

N. B. Dhar, T. M. Kessler, R. D. Mills, F. Burkhard, und U. E. Studer.

Nerve-sparing radical cystectomy and orthotopic bladder replacement

in female patients.

Eur Urol, 52 (4): 1006–1014, Oct 2007.

doi: rm10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.048.

URL https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.048.

Nagele, U.; Kuczyk, M.; Anastasiadis, A. G.; Sievert, K.; Seibold, J. & Stenzl, A.

Radical cystectomy and orthotopic bladder replacement in females.

Eur Urol, 2006, 50, 249–257

Ozyuvaci u.a. 2005 OZYUVACI, E. ; ALTAN, A. ;

KARADENIZ, T. ; TOPSAKAL, M. ; BESISIK, A. ;

YUCEL, M.:

General anesthesia versus epidural and general anesthesia in radical

cystectomy.

In: Urol Int

74 (2005), Nr. 1, S. 62–7

Deutsche Version: Radikale Zystektomie

Deutsche Version: Radikale Zystektomie

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.