You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > Retropubic radical prostatectomy

Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy: Surgical Technique and Complications

Indications for Radical Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy (RPE) is the gold standard of curative therapy in patients with localized prostate cancer and a life expectancy of at least 10 years. For a detailed description of the surgical treatment indications and results see:

Contraindications to Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy

Absolute contraindications are uncorrected coagulation disorders and untreated urinary tract infections. Further contraindications depend on the surgical risk due to the comorbidity of the patient and the impact of prostatectomy on the life expectancy of the patient.

Surgical Technique of Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy

Preoperative Patient Preparation

Timing of surgery:

A nerve-sparing prostatectomy should be performed no earlier than eight weeks after prostate biopsy and three months after TURP. The interval leads to reduced adhesions between the prostate and neurovascular bundle.

Autologous blood donation:

There is no contraindication from an oncological point of view. Autologous blood donations are associated with substantial costs and, due to the low transfusion risk, are often unnecessary.

Bowel preparation:

The day before surgery: clear liquid diet and an enema before sleeping.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis:

Before skin incision, e.g., 2nd generation cephalosporin. See also section perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis.

Patient positioning:

Supine position with slight hyperextension of the lumbar spine. Disinfection and draping. Insert a 16 Fr Foley catheter with 30 ml balloon inflation.

Anesthesia:

General anesthesia is the rule, spinal anesthesia is possible if lymphadenectomy is unnecessary.

Surgical Approach:

Lower midline incision. Cut the linea alba. Blunt dissection of the retropubic space, the peritoneum is pushed off cranially. Identify the iliac vessels, ureters, and tesicular vessels. Insert a self-retaining surgical retractor.

|

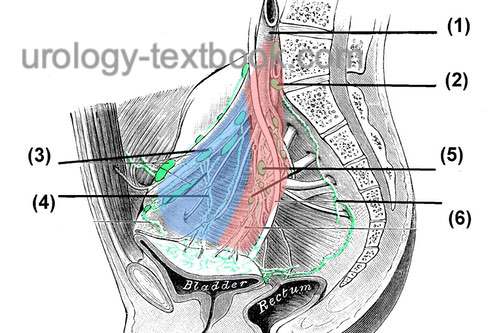

Bilateral Pelvic Lymphadenectomy:

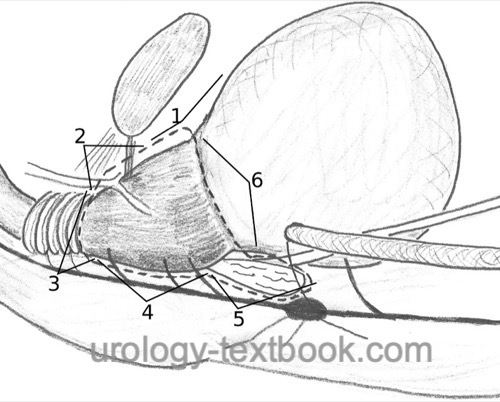

Lymphadenectomy can be omitted in patients with low-risk prostate cancer (PSA <10 ng/ml and Gleason ≤6); otherwise, staging lymphadenectomy is considered standard of care during prostatectomy [fig. Situs before pelvic lymphadenectomy]. Dissection borders are laterally the external iliac artery, caudally the superior ramus of the os pubis, medially the obliterated umbilical artery and the urinary bladder, dorsally the obturator nerve and the pelvic wall, cranially the ureter and the bifurcation of the common iliac artery [fig. template for pelvic lymphadenectomy]. Use a careful dissection technique with bipolar coagulation, application of clips or thin ligatures to lower the complication rate due to lymphoceles. For extended lymphadenectomy, the dissection field reaches the aorta, internal iliac artery, and the presacral lymph nodes. The survival benefit for extensive lymphadenectomy is unclear, but it is an option in high-risk patients.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

|

Approach to the Prostate:

Displace the bladder and peritoneum cranially and posteriorly with the retraction system. Cleanse the prostate from covering fatty tissue, coagulate, and transect interfering superficial veins [fig. RRP (1)]. Coagulate and transect the puboprostatic ligament after incision of the endopelvic fascia [fig. puboprostatic ligament]. Bluntly expose the apical area of the prostate with a dissecting swab.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

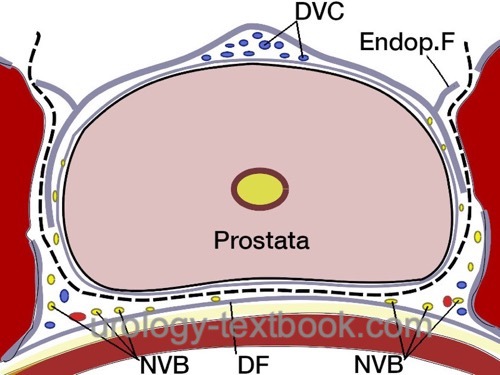

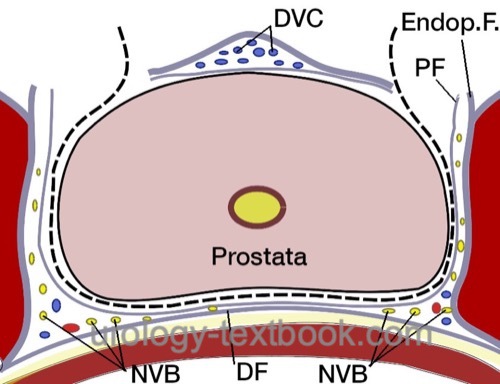

Transection of the Dorsal Venous Complex:

Use a Babcock clamp to bunch the dorsal venous plexus over the apex of the prostate and place a suture ligation [fig. DVC 1]. Repeat the procedure for the venous plexus on the prostate near the bladder neck against retrograde bleeding. Transect the dorsal venous complex gradually down to the urethra [fig. DVC 2], close bleeding vessels with bipolar coagulation or with sutures. The dissection line must find the plane just below the dorsal venous complex. Do not penetrate the prostate; there is a risk of R1 resection in tumors of the anterior fibromuscular stroma [fig. RRP (2)].

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Preservation of the Neurovascular Bundles:

Open the fascia overlying the prostate to isolate the nerve bundle laterally [fig. nerve sparing]. Use clips to stop bleeding before cutting the fascia. Depending on the patient's wishes and tumor stage, nerve-sparing can be performed to a varying extent; see the following figures. The intrafascial technique results in better erectile function, but the additional risk for R1 resection is controversial.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

|

|

Division of the Urethra:

Transect the ventral portion of the urethra until the catheter is visible [fig. RRP (3)]. Place anastomotic sutures at the 9, 11, 1, and 3 o'clock positions (double-armored sutures such as PDS 2-0 or Vicryl 2-0 with 5/8 needle) [fig. anastomosis]. Clamp the bladder catheter in the opened urethra, discard the valve piece, and use the intact balloon inflation of the catheter as a mobilization aid for further dissection. Transect the dorsal urethra and the dorsal portion of the external sphincter, which attaches to the prostate apex. Place two anastomotic sutures at the 5 and 7 o'clock positions. Additional sutures may be placed through the dorsal sphincter apparatus, which later grasp the bladder neck and Denovillier fascia, to improve early continence and tightness of the anastomosis (Rocco et al., 2009).

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Ascending Dissection of the Prostate:

Develop the layer between the rectum and the prostate with blunt and sharp dissection. Separate the neurovascular bundle from the prostate with the overholt, transect vessels to the prostate between clips [fig. pedicles] [fig. RRP (4)]. Retract the prostate cephalad using the catheter to identify the prostate pedicles and transect the pedicles step by step between clips.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Dissection of the Seminal Vesicles:

The ascending dissection exposes the seminal vesicles, which become visible under the Denonvilliers fascia. After incision, mobilize the seminal vesicles and clip and transect supplying vessels [fig. seminal vesicle dissection]. Stay close to the seminal vesicle; otherwise, injury to the neurovascular bundle lateral to the tip of the seminal vesicles is possible [fig. RRP (5)]. Isolate and transect both vas deferens between clips. After complete mobilization, retract the seminal vesicles and both vas deferens cephalad to expose the dorsal bladder neck. Dissect the bladder neck with curved (Satinsky) scissors.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Descending Dissection of the Prostate:

The descending dissection can replace the ascending dissection at any time if the anatomy is unclear; some authors also promote the primary descending preparation. Prior to primary descending dissection, the neurovascular bundle is isolated by an incision of the fascia overlying the prostate, which is analogous to ascending dissection.

Bladder Neck Dissection:

Spare or resect the bladder neck, depending on the tumor stage. The border between the bladder neck and the prostate appears clearly with traction on the catheter [fig. bladder neck] [fig. RRP (6)]. Bipolar coagulation is sufficient for bleeding. The circular muscle fibers of the bladder neck help to find the correct plane. Bladder neck reconstruction is unnecessary after sparing the bladder neck during the final dissection steps. If the bladder neck is too wide, it is narrowed by sutures at 6 o'clock ("tennis racket suture") and the bladder mucosa is inverted with thin sutures. Beware of the ureteric orifices.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Vesicourethral Anastomosis:

Insert a new 20 CH Foley catheter into the bladder. Place the anastomotic sutures (already prepared during apical dissection) at the corresponding bladder neck location [fig. anastomosis]. Knot the sutures from dorsal to ventral. Irrigate the bladder after anastomosis to eliminate clots and to check for anastomosis leakage.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Wound Closure:

- Irrigate the operative field and check for bleeding.

- Insert a wound drainage (e.g., closed gravity system)

- Close the rectus sheath with running suture (USP 1). Proceed with subcutaneous interrupted sutures and a subcuticular skin suture.

Postoperative Care after Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy

- General measures: consider patient-controlled analgesia for pain management. Early mobilization and exercises to prevent thrombosis and pneumonia. Thrombosis prophylaxis. Laboratory tests (hemoglobin, creatinine), regular physical examination of the abdomen, and incision wound.

- Diet advancement: clear liquid diet on day one, soft food diet the following days until bowel movement.

- Drains and catheters: keep drain until drainage is below 30 ml/24 h. Check for anastomotic leakage with cystography and remove the catheter after seven days. Depending on bladder neck resection and reconstruction extent, the catheter should stay for 10–14 days before the first cystography.

Complications of Retropubic Radical Prostatectomy

Bleeding:

The blood loss after radical retropubic prostatectomy is around 700 ml, the transfusion rate is less than 5%.

Lymphocele:

The frequency of lymphoceles depends on the extent of lymphadenectomy [fig. pelvic lymphoceles]. Avoid lymphoceles by careful ligation or clipping of the lymphatic vessels, limited lymphadenectomy, sparing the lymphatic vessels of the lower extremity along the external iliac artery, and injection of heparin exclusively into the upper extremity. Therapy consists of percutaneous drainage or laparoscopic fenestration.

|

Rectal Injury:

If noted during the prostatectomy, close the rectal injury in two layers. If possible, cover the suture with omentum majus. A temporary anus praeter is necessary in case of insufficiency of the repair. Risk factors for rectal injury include advanced tumor stage, previous surgery or radiotherapy of the prostate. Rectal injury or impaired healing can also lead to a rectourethral fistula. Clinical signs include pneumaturia and flocculent urine. Fecal incontinence is rarely possible.

|

Urinary Incontinence:

Urinary incontinence is common immediately after surgery; you can expect spontaneous improvement for 1--2 years. In the long term, about 10% of patients require more than one pad. Pelvic floor exercises (with or without biofeedback) help improve early continence, but the effect on late continence is unclear (MacDonald et al., 2007). Risk factors for postoperative incontinence include age over 70 years, previous TURP, or advanced tumors. For urinary incontinence treatment, see section male stress urinary incontinence.

Erectile Dysfunction:

Prostatectomy results in significant deterioration of erectile function. Controlled studies have described long-term potency rates as low as 30% after bilateral nerve preservation. ED Therapy with oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors additionally enables sexual intercourse in 20% of patients (50% overall). Long-term postoperative potency may be improved by early administration of oral phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Whether early administration should be permanent or given as needed is controversial (Montorsi et al., 2008). Predictors of postoperative potency are bilateral nerve-sparing, sexually active young patients with good preoperative potency, PSA <10 or Gleason <8 (low tumor burden).

Inguinal Hernia:

The risk of inguinal hernia is up to 15% after prostatectomy versus 3% in the control group without surgery, inguinal hernia usually develops within the first two years (Zhu et al., 2013). The prospective-controlled LAPPRO study found no relevant differences (7.3–8.4% hernia risk) after open-surgical or robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (Nilsson et al., 2022).

Further Complications:

Wound infections, anastomotic stricture, anastomotic leakage, ureteral injury, penile shortening, ileus. Cardiovascular complications: thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction. Mortality is 0.4%, and the major cause is pulmonary embolism.

|

| Simple retropubic prostatectomy | Index | Laparoscopic pelvic lymphadenectomy |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

P. Dell’Oglio, A. Mottrie, and E. Mazzone, “Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy vs. open radical prostatectomy: latest evidences on perioperative, functional and oncological outcomes.,” Current opinion in urology, vol. 30, no. 1, pp. 73–78, 2020, doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000688.

Graefen u.a. 2006 GRAEFEN, M. ; WALZ, J. ;

HULAND, H.:

Open retropubic nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

In: Eur Urol

49 (2006), Nr. 1, S. 38–48

Montorsi, F.; Brock, G.; Lee, J.; Shapiro, J.; Poppel,

H. V.; Graefen, M. & Stief, C.

Effect of nightly versus on-demand

vardenafil on recovery of erectile function in men following bilateral

nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy.

Eur Urol, 2008,

54, 924-931.

H. Nilsson et al., “Risk of hernia formation after radical prostatectomy: a comparison between open and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy within the prospectively controlled LAPPRO trial.,” Hernia, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 157–164, 2022, doi: 10.1007/s10029-020-02178-7.

Rocco, F. & Rocco, B.

Anatomical reconstruction

of the rhabdosphincter after radical prostatectomy.

BJU Int, 2009,

104, 274-281.

J. A. Smith, S. S. Howards, G. M. Preminger, and R. R. Dmochowski, Hinman’s Atlas of Urologic Surgery Revised Reprint. Elsevier, 2019.

Zhu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xie, L.; Chen, J. & Niu, Y.

Risk

Factors and Prevention of Inguinal Hernia after Radical Prostatectomy: A

Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

J Urol, 2012.

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der retropubischen radikalen Prostatektomie

Deutsche Version: Technik und Komplikationen der retropubischen radikalen Prostatektomie

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.