You are here: Urology Textbook > Urologic examinations > Laboratory tests > Semen analysis

Semen Analysis: Technique and Normal Values of the Parameters

Semen analysis is indicated for diagnosing male infertility and planning assisted fertilization. Sperm analysis is unreliable for diagnosing fertility: men can father children with a pathological sperm test. However, no paternity is guaranteed in case of a normal sperm test. Premature andrological diagnosis can lead to overdramatization in impatient couples with the risk of overtreatment. Infertility is defined as the absence of pregnancy despite regular unprotected intercourse over 1 to 2 years. The methodology and standard values are presented according to WHO recommendations (WHO, 2010).

Procedure Steps of Semen Analysis

A complete collection of semen is fundamental for a correct analysis. Two days of sexual abstinence are recommended before the collection of the specimen.

After collection, the semen is stored in an incubator at 37 degrees Celsius. After 30–60 minutes, the consistency and appearance of the sperm are examined. After complete liquefaction, the volume and the pH are measured. In a first microscopic examination, the morphology and mobility of spermatozoa are assessed, and the dilution for the sperm count is set. After dilution of the semen and counting of the spermatozoa concentration, a smear specimen of semen is made for staining. The morphology of sperm is examined with the stained semen specimen. The WHO recommends the Papanicolaou, the Shorr, or the Diff-Quick staining. Depending on the findings and clinical information, special investigations are initiated (vitality testing, inflammation and immunological tests, measurement of fructose), or the semen can be used for cryopreservation.

Normal Findings and Differential Diagnosis of Semen Analysis

Gross Appearance of Semen:

Immediately after ejaculation, the semen is usually a coagulum of various consistencies. The semen liquefies within minutes at room temperature or in an incubator; some parts of the specimen may take longer and make the semen difficult to analyze. Normal liquid semen has a homogeneous, gray-opaque color. It is less opaque if the sperm concentration is low. Some diseases cause a change in semen color: red-brown (hematospermia) or yellow (jaundice, intake of vitamins or drugs).

Consistency of the Semen

Normal semen liquefies within 60 min; after that time, the falling drops from the pipette tip should be shorter than 2 cm. Inadequate liquefaction can distort further investigation; with repeated pipetting, the semen is homogenized and mixed.

Semen Volume:

The normal semen volume should be > 1.5 ml. The WHO recommends to determine the volume by weighing the vials before and after sperm collection. The specific weight of semen is approximately 1 g per ml. Differential diagnosis of reduced semen volume (DD hypospermia):

- Incomplete semen collection

- Retrograde ejaculation

- Obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts

- Hypogonadism

The pH of the Semen:

The normal pH of semen is 7.2 to 8.0. For pH determination, the sperm must be liquid, the range of the indicator paper should be between pH 6–10.

An acidic pH of semen (with azoospermia and reduced semen volume) is caused by prostatic secrets only and is an indicator of ejaculatory duct obstruction or malformations of the seminal tract (e.g., missing seminal vesicles). An infection can cause a basic pH of >8.0.

Microscopic Examination of the Fresh Specimen

A well-mixed drop of semen (10 μl) is assessed on a slide under a cover glass (22 × 22 mm) with 200–400X magnification.

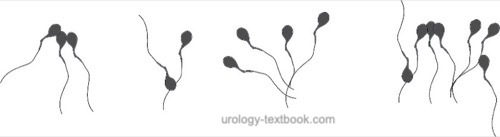

Agglutination of Motile Spermatozoa:

Sperm agglutination refers to the clumping of mobile spermatozoa [see figure sperm agglutination].

|

Agglutination of spermatozoa suggests the existence of anti-sperm antibodies. The agglutination of mobile spermatozoa to each other has to be separated from the non-specific adherence of immobile spermatozoa and the adherence of motile spermatozoa to epithelial cells or debris. The extent and nature of agglutination should be judged with the following graduation:

- Grade 1 (isolated): <10 spermatozoa per agglutinate, many free mobile sperm

- Grade 2 (moderate): 10–50 spermatozoa per agglutinate, many free mobile sperm

- Grade 3 (strong): agglutinates with >50 spermatozoa, only a few free mobile spermatozoa

- Grade 4 (complete): completely agglutinated spermatozoa, no mobile free spermatozoa visible

Additional Cells:

Next to spermatozoa, the semen may also show epithelial cells and round cells, which can be leukocytes or immature germ cells. The further differentiation of round cells is made by staining with the peroxidase: peroxidase-positive cells are leukocytes.

Assessment of sperm motility:

The motility of sperm is best assessed immediately after the liquefaction of the semen. The thickness of the liquid layer between the slide and cover glass should be 20 microns; this correlates with a well-mixed drop of sperm (10 μl) under a cover glass of 22 × 22 mm. The motility should be examined with 200–400X magnification: 200 spermatozoa are assessed for motility and classified using the following graduation:

- Progressive motility (PR): active linear or slightly curved forward movement.

- Non-progressive motility (NP): no forward movement or circular forward movement

- Immotility (IM): no visible movement

At least two sets of 200 spermatozoa on two slides should be classified using the abovementioned graduation; the results should be comparable. The results of both tests are averaged and given in percent. Reference values for motility: >40% motile sperm (PR + NP), >32% progressive motility.

Asthenozoospermia is the medical term for reduced sperm motility: the percentage of progressively motile sperm is below 32%. Causes of asthenozoospermia are insufficient liquefaction, autoantibodies, inflammation, and disorders of the sperm tails. Causes of false-negative asthenozoospermia are cold sperm, old sperm, or sperm collection with contamination (e.g., soap).

Assessment of vitality:

If over 40% immobile spermatozoa are seen, perform a vitality test with eosin staining. The dye enters dead sperm within 1 minute, which leads to red sperm heads in microscopy. Sperm heads without dye are considered vital. 200 spermatozoa should be classified, and the standard value for vital spermatozoa is >58%. As an internal control, the proportion of dead sperm should not be higher than the immobile sperm proportion. More than 42% of dead sperm is called necrozoospermia, often caused by epididymal disease or inflammation.

Sperm Count:

Total sperm count correlates with time to pregnancy and pregnancy rate. After determining the sperm concentration using the hemocytometer (two sets of 200 sperm should be counted), the sperm concentration is used to calculate the total sperm count with the help of the semen volume. Standard values: >15 × 106 spermatozoa per ml or >39 × 106 total sperm count.

Oligozoospermia:

Oligozoospermia (oligospermia) refers to semen with a reduced sperm concentration: <15 × 106 per ml or <39 × 106 total sperm count.

Cryptozoospermia:

Spermatozoa cannot be observed in a fresh semen sample. However, spermatozoa can be found after centrifugation and microscopy of the sperm pellet.

Azoospermia:

Azoospermia refers to semen without spermatozoa. Azoospermia should only be diagnosed after centrifugation of the ejaculate and microscopy of the sperm pellet.

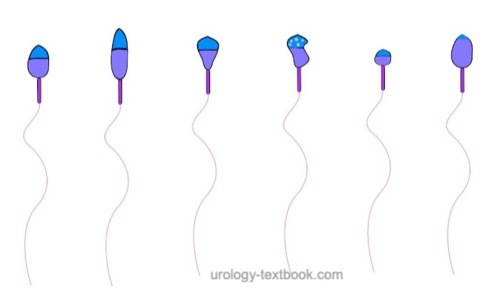

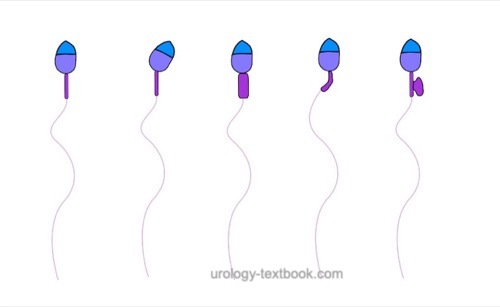

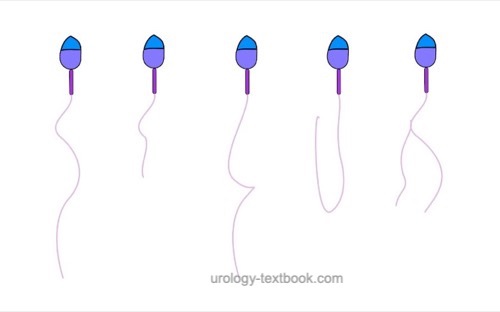

Sperm Morphology:

The assessment of sperm morphology should be done with 1000 × magnification and (e.g.) Giemsa stain of dried smear specimen of sperm. The criteria for the classification of normal and pathological morphology are presented in the figures \ref{kopfdefekte}, \ref{halsdefekte} und \ref{schwanzdefekte}.

|

|

|

Teratozoospermia:

Morphologically normal spermatozoa are normally less than 25%. Teratozoospermia refers to semen with less than 4% morphologically normal spermatozoa. Optionally, the location of the defect can be specified: % head defects, % midpiece defects, % sperms with cytoplasmatic droplets and % tail defects.

Tests for Inflammation:

Evidence for infection of the seminal ducts provides the count of peroxidase-positive cells (normal <1 × 106 cells per ml), elastase (normal <250 ng/ml), a positive sperm culture, or evidence of bacterial prostatitis. The importance of inflammation tests is controversial.

Pyospermia:

Pyospermia is a high number of white blood cells in the sperm (>106 peroxidase-positive cells per ml). A urinary tract infection should be ruled out. Significant bacteriospermia is if >103 bakteria/ml sperm are found.

Immunological tests:

Anti-sperm antibodies cause the agglutination of spermatozoa, which is seen in fresh semen preparation (see above), this indicates further immunological studies. Anti-sperm antibodies (ASA) can be detected with the MAR test (mixed antiglobulin reaction test) or the Immunobeads test. Detailed description of the procedures please refer to the current WHO manual (WHO, 2010). The standard value of the MAR test: less than 50% of mobile sperm are MAR positive. The diagnostic value of the MAR test is controversial, and effective therapeutic interventions are unavailable.

Fructose in Semen:

The normal concentration of fructose in semen is >13 mmol/l in the seminal plasma (supernatant after centrifugation of liquid semen). Obstruction of the ejaculatory ducts causes decreased seminal fructose concentrations.

| Examinations | Index | Karyotyping |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

World Health OrganisationCooper, T. G. (ed.) WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen

WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland, 2010

Deutsche Version: Spermiogramm

Deutsche Version: Spermiogramm

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.

New release: The first edition of the Urology Textbook as an e-book—ideal for offline reading and quick reference. With over 1300 pages and hundreds of illustrations, it’s the perfect companion for residents and medical students. After your 7-day trial has ended, you will receive a download link for your exclusive e-book.