You are here: Urology Textbook > Surgery (procedures) > TURP

TURP: Technique and Complications of Transurethral Prostate Resection

Transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) is the endoscopic removal of prostate tissue using an electrified wire loop (Alschibaja et al., 2005). Despite modern endoscopic alternatives, TURP is the most commonly performed procedure for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

|

Indications for transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

Surgical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia is necessary in cases of recurrent urinary retention, recurrent urinary tract infections, recurrent hematuria, bladder stones, postrenal acute kidney injury, and large bladder diverticula. The most common indication for TURP is moderate to severe symptoms of BPH, which are inadequately relieved with medication and limit the patient's quality of life. TURP is used for a maximum prostate gland size of 75–120 ml.

|

Contraindications for Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

Low life expectancy, coagulation disorders, urinary tract infections. Consider simple prostatectomy for very large adenomas (> 75–120 ml), urinary bladder diverticula requiring surgery, urinary bladder stones, complex urethral disease (after hypospadias surgery), and contraindication for lithotomy position.

Surgical Technique of the Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

Reducing the risk of bleeding

The bleeding during TURP may be reduced by medication with finasteride or dutasteride. The effect is based on lowering microvessel density; the result will become significant after one to several months of therapy.

Anesthesia for TURP

Spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia is recommended. Spinal anesthesia offers theoretical advantages in the initial postoperative period: the patient is immobilized, manipulations with the catheter are possible without pain, and there is less pressing and coughing after surgery. Randomized studies have found no difference in bleeding volume.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis

Several randomized trials found benefits for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis using cephalosporins or aminopenicillins with penicillinase inhibitors. In particular, patients with risk factors for urinary tract infection benefit (diabetes, urinary bladder stones, urinary retention with catheter). Perioperative antibiotics reduce the rate of postoperative urinary tract infections and fever and may reduce the risk of urethral strictures.

Intraoperative preparations:

Lithotomy positioning, suprapubic shaving if necessary, disinfection of external genitals, lower abdomen, and perineum, sterile draping with rectal shield, and provision of body-warm irrigation solution.

Cystoscopy

Check the urethral width and prostate size, and exclude bladder pathology (stones, diverticulum, or carcinoma) with a cystoscopy. Place a suprapubic catheter for additional drainage (14 CH) and postoperative management, especially for patients with large prostate gland size or large postvoid residual volume.

Internal Urethrotomy

24 CH instruments usually fit through the urethra without problems and should be used to resect even large glands. Short-distance urethral strictures are treated by internal urethrotomy with direct vision. However, if the anterior urethra is too narrow to accommodate the instrument, a perineal urethrostomy can be performed to insert the instrument. As an alternative, blind urethrotomy over the narrow segment of the urethra may be performed. With larger instruments (28 CH), prophylactic blind urethrotomy was recommended to prevent ischemic damage and consecutive urethral stricture.

|

|

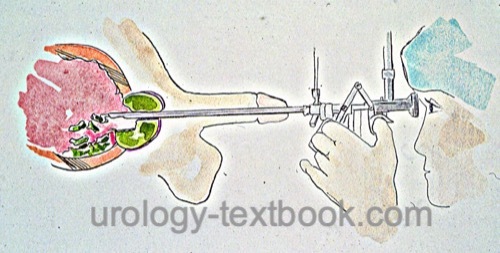

Resectoscope:

A resectoscope is a combination of a cystoscope and an electrosurgical instrument, which enables the resection of the prostate with an electrically activated wire loop [figure resectoscope]. Continuous irrigation is necessary for endoscopic vision impaired by the bleeding of the prostate during the procedure. In low-pressure resection, the irrigation fluid is drained via a suprapubic trocar. A two-channel resectoscope is an alternative, with one channel for irrigation and the other for drainage. Disadvantages are, however, the diameter of the instrument and less reliable drainage of the irrigation fluid.

Electrocautery

Monopolar current is used in standard TURP, with different cutting and coagulation programs comparable to open surgery. The coagulation effect is produced by the current flow from the resection loop through the prostate tissue to the return electrode. The irrigation solution used in transurethral resection with monopolar current must be salt-free to prevent current flow through the irrigation fluid. The salt-free irrigation fluid harbors a risk for TUR syndrome if large amounts of fluid enter the circulation (see below).

|

It is essential to avoid unnecessarily high current power, as collateral damage to the sphincter of the urethra and the cavernous nerve is possible. The patient's padding must be kept dry to prevent burns. Bipolar resection with isotonic saline irrigation is an excellent alternative to monopolar TURP.

Different wire loops and electrodes:

Various wire loops and electrodes have been developed to improve cutting, coagulation, and vaporization. Technical variations are thicker loops (band loop), rollerballs, grooved vaporization roller, or Collins knife electrodes [figure different resection electrodes].

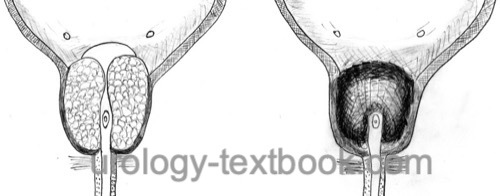

Mauermayer Resection Technique

The middle lobe is resected, and a channel between the five and seven o'clock positions is formed at the prostatic floor. After that, with good irrigation conditions, the side lobes and ventral parts are resected. The apical region of the gland is resected last [fig prostate resection (TURP)] (Mauermayer, 1985).

|

Nesbit Resection Technique

The resection starts at the twelve o'clock position until the surgical capsule. Next, the ventral portions of the prostate gland are resected until nine o'clock and three o'clock positions. The resection of the posterior quadrants is the next step, and the apical parts of the gland are resected last (Nesbit, 1951).

Apical Resection

The apical resection is the most critical step for the success of prostate resection. An insufficient apical resection does not remove the obstruction. On the other hand, the external sphincter of the bladder is in close anatomical proximity and may be injured by excessive apical resection.

The anatomical landmark for the apical resection is the seminal colliculus (verumontanum). The adenoma is removed, preserving the verumontanum. The resection starts at the six o'clock position (with the verumontanum in sight) and is carried out circularly. An unintentional slippage of the resectoscope during resection has to be avoided, or damage to the sphincter can quickly occur. This is especially true for the resection at the twelve o'clock position, as the verumontanum is not in sight.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Ejaculation-preserving TURP:

The preservation of para-collicular tissue (minimum 10 mm laterally and proximally of the colliculus seminalis) is essential to avoid postoperative retrograde ejaculation. The resection of the middle and lateral lobes is comparable to standard TURP. Still, avoid a deep resection between the bladder neck and para-collicular tissue between the 5 and 7 o'clock position to spare the posterior longitudinal musculature of the urethra (Musculus ejaculatorius).

Removal of the Resection Chips

Use a bladder syringe or Ellik-Evacuator to remove all resection chips from the bladder. Raise the instrument (stand up!) so that the shaft moves in the direction of the trigone of the bladder. The cystoscopic control of the complete removal avoids postoperative problems like catheter blockage, urinary retention or infections.

Continuous Irrigation Catheter

After the resection and removal of all resection chips, insert a 20–24 CH irrigation catheter. Inflate the balloon with at least 20 ml in the prostatic fossa. Increased balloon inflation can control venous bleeding (maximum additional 1 ml per gram resected tissue). The bladder is an alternative position for the catheter balloon (50–80 ml balloon inflation). Control bleeding with a slight traction on the catheter, which pulls the catheter balloon against the bladder neck.

Postoperative Management after transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)

- Continuous irrigation for 12–24 hours

- Remove the catheter after 2–3 days

- Control complete bladder emptying with a suprapubic catheter or ultrasound imaging

Intraoperative Complications of TURP

Bleeding

Stop arterial bleeding using electrocautery by the end of the operation. New arterial bleedings in the postoperative course require repeated endoscopic hemostasis. Venous bleeding is more problematic to stop by electrocautery; it is better managed with the irrigation catheter balloon positioned in the prostatic fossa or bladder (see above the placement of the catheter). Bleeding requiring transfusion should rarely occur, with transfusion rates around 4%.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Perforation of the Prostatic Capsule

Deep resection can result in perforation of the prostate capsule with extravasation of the irrigation fluid. If not noted, perforation and extravasation lead to nausea, vomiting, tense abdomen, lower abdomen, and back pain despite intraoperative spinal anesthesia. The development of TUR syndrome is likely (see below).

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

TUR Syndrome

The intrusion of salt-free irrigation fluid in open veins or perforation of the prostate capsule can cause a volume overload and dilutional hyponatremia (<125 mmol/l).

Signs and symptoms of the TUR syndrome:

Signs and symptoms of a TUR syndrome are confusion, nausea and vomiting, arterial hypertension, bradycardia, pulmonary edema, and impaired vision. The frequency is 2%, and the risk factors for TUR syndrome are a prostate volume over 45 ml, a resection time over 90 min, and the height of the irrigation fluid over 70 cm.

Diagnosis and therapy of the TUR syndrome:

Early detection of TUR syndrome is possible with intraoperative sodium controls (venous blood gas analysis). In case of clinical suspicion of a TUR syndrome, furosemide is given (20–40 mg i.v.). It is vital to end the operation quickly and to reduce the height of the irrigation fluid during coagulation. With proven hyponatremia, hypertonic NaCl solution is infused slowly. Depending on the severity of TUR syndrome, intensive care monitoring is necessary.

Injury to Adjacent Organs

- Injury to the external sphincter of the bladder, resulting in stress urinary incontinence

- Excessive resection at six o'clock, especially with a large middle lobe, can undermine the bladder neck.

- Injury to the trigone of the bladder and ureter ostium.

- Unusual is the perforation into the rectum.

Postoperative Complications of TURP

Bleeding

Postoperative Hematuria usually stops within three weeks after TURP. Recurrent hematuria, clot retention, and bladder tamponade are possible in up to 20%. Physical rest is necessary for four weeks.

Retrograde Ejaculation

Retrograde Ejaculation is common after standard transurethral resection of the prostate (60%). The preservation of the peri-montanal tissue (around the colliculus seminalis) reduces the risk down to 10%.

Urinary Tract Infections

The cause for postoperative urinary tract infections is an ascending catheter infection and the (already existing) bacterial colonization of the prostate (risk factor urinary retention with bladder catheter). Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the likelihood of infectious complications. An epididymitis occurs in 2%.

Micturition

Urinary incontinence (up to 10%), mostly mild and self-limiting. Persistent urinary retention, 2.5% are discharged from the hospital with a catheter.

Bladder Neck Stricture

Bladder Neck Stricture in 2–10%. Risk factors are large prostate volume, missing bladder neck incision, blood transfusions, and poor micturition after resection.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Urethral Stricture

Urethral strictures are reported up to 10%. Urethral strictures can be avoided with a thin resection shaft (24 CH), limiting the time of the transurethral catheter and applying prophylactic antibiotics.

Cardiac Complications

Myocardial infarction in 1%, perioperative mortality in 0.2%.

| Prostate biopsy | Index | Endoscopic Enucleation of the Prostate (HoLEP) |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Alschibaja u.a. 2005 ALSCHIBAJA, M. ; MAY,

F. ; TREIBER, U. ; PAUL, R. ; HARTUNG, R.:

[Transurethral resection for benign prostatic hyperplasia current

developments].

In: Urologe A

44 (2005), Nr. 5, S. 499–504

N. Couteau, I. Duquesne, and Fré, “Ejaculations and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: An Impossible Compromise? A Comprehensive Review.,” J. Clin Med, vol. 10, no. 24, 2021.

Mauermayer 1985 MAUERMAYER, W.:

[Operative complications in transurethral operations: causes and

prevention].

In: Urologe A

24 (1985), Nr. 4, S. 180–3

Nesbit 1951 NESBIT, R. M.:

Transurethral prostatic resection: a discussion of some principles

and problems.

In: J Urol

66 (1951), Nr. 3, S. 362–72

M. Rieken, T. Antunes-Lopes, B. Geavlete, T. Marcelissen, E. Y. A. U. F. Urology, and B. Group, “What Is New with Sexual Side Effects After Transurethral Male Lower Urinary Tract Symptom Surgery?,” Eur. Urol. Focus, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 43–45, 2018.

Deutsche Version: Transurethrale Resektion der Prostata (TURP)

Deutsche Version: Transurethrale Resektion der Prostata (TURP)

Urology-Textbook.com – Choose the Ad-Free, Professional Resource

This website is designed for physicians and medical professionals. It presents diseases of the genital organs through detailed text and images. Some content may not be suitable for children or sensitive readers. Many illustrations are available exclusively to Steady members. Are you a physician and interested in supporting this project? Join Steady to unlock full access to all images and enjoy an ad-free experience. Try it free for 7 days—no obligation.