You are here: Urology Textbook > Ureters > UPJ obstruction

Ureteropelvic Junction (UPJ Obstruction): Diagnosis and Treatment

Definition of UPJ Obstruction

The ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) is between proximal ureter and renal pelvis. Congenital malformations with obstruction of the ureteropelvic junction are a common cause of hydronephrosis [fig. UPJ obstruction]. Review literature: (Tan and Smith, 2004).

|

Epidemiology of UPJ Obstruction

Neonatal period:

A ureteropelvic obstruction causes up to 48% of fetal hydronephrosis.

Postnatal period:

The Incidence of UPJ obstruction is 1:1500. 60% on the left side and 10–40% of cases involve both kidneys. Male to female ratio is 2:1 in the neonatal age group.

Etiology of UPJ obstruction

Ureteral causes:

Insufficient tubularisation of the proximal ureteral segment in the 10th to 12th week of pregnancy obstructs of the UPJ, probably caused by a lack of innervation or imbalance of growth factors. This leads to a disturbed structure of the smooth muscles within the ureteral wall and insufficient peristalsis of the proximal ureteral segment. Rare intrinsic causes are ureteral valves or polyps.

Extrinsic causes:

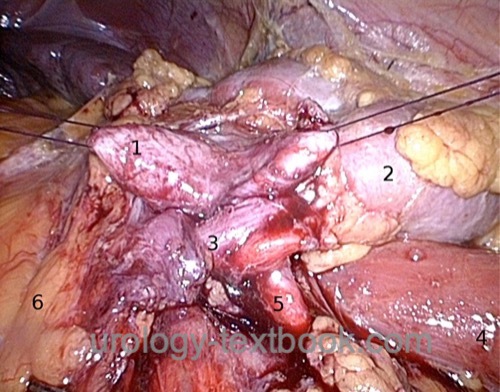

- Compression of the ureter by a lower pole renal artery (15–40%) or by fibrotic strands [fig. intraoperative findings of a UPJ obstruction].

- Commonly associated malformations: pelvic kidney, horseshoe kidney, renal malrotation, double renal systems.

|

Secondary UPJ obstruction:

In 10% of patients with severe vesicoureteral reflux, UPJ obstruction exists (or develops).

Pathophysiology of UPJ obstruction

Increased resistance of the urinary flow:

The obstruction leads to a chronic increase of pressure in the renal pelvis, which leads to smooth muscle hypertrophy, dilatation of the renal pelvis, and increased renal intratubular pressure.

Loss of Renal Function:

The increased renal pressure decreases renal blood flow (RBF) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The reduced urine production normalizes the pressure within the renal pelvis, which remains dilated. An uncorrected UPJ obstruction may lead to functionless hydronephrosis. An activated RAAS system seems to be the central mediator of the pathophysiological effects (reduction of RBF and GFR). The administration of ACE inhibitors has a protective effect on renal function.

Signs and Symptoms of a UPJ Obstruction

Newborns and infants:

Abdominal tumor, failure to thrive, and urosepsis are the classic presentation. Nowadays, many (more) children are diagnosed via prenatal ultrasound imaging, and many of them are asymptomatic.

In children and adults:

Flank or upper abdominal pain, often with nausea and vomiting, particularly after fluid intake. Further symptoms are pyelonephritis and hematuria.

Diagnosis of UPJ Obstruction

Renal ultrasound:

With renal ultrasound, differentiation between physiologic dilatation and significant hydronephrosis is impossible. The anteroposterior diameter of the renal pelvis is used as a parameter for the extent of obstruction of the UPJ obstruction.

With an anteroposterior diameter of the renal pelvis of 12 mm three months after birth, renal scintigraphy should be initiated. The ap diameter three months after birth is also a risk factor for future necessary operation: 75% of children with an anteroposterior diameter of the renal pelvis of more than 21 mm will need an operation. Doppler ultrasound may reveal an increased resistive index (RI, usually about 0.7) in the affected kidney.

Intravenous urography:

- Dilatation of the renal pelvis and calyceal system with a stenotic ureteropelvic segment.

- Delayed drainage of contrast medium from the renal pelvis.

- Intravenous urography is often replaced by better alternatives (e.g., MR urography or CT).

Renal scintigraphy:

After administration of a radionuclide (MAG3), renal scintigraphy assesses renal function separately for each kidney and measures the drainage from the renal pelvis to the bladder after stimulation with furosemide. Poor drainage from the renal pelvis and, therefore, significant hydronephrosis means a tracer washout of less than 50% within 20 minutes after furosemide stimulation. A tracer washout half-time of fewer than 10 minutes after furosemide stimulation is considered normal. A half time between 10–20 min is considered uncertain to relevant obstruction. Indications for surgery are relevant obstruction, especially with symptoms or decreasing fractional renal function (<40%).

Voiding cystourethrogram:

Vesicoureteral reflux is associated in 10% of cases with UPJ obstruction. A voiding cystourethrogram is indicated for dilated ureters.

Retrograde pyelography:

Retrograde pyelography and ureteroscopy are indicated for unclear proximal ureteral stenoses, before ureteral stenting in patients with symptomatic obstruction, and before surgery to confirm the diagnosis depending on available imaging [figure retrograde pyelography of UPJ obstruction in a duplex system and retrograde pyelography of UPJ obstruction].

|

|

CT or MRI angiography and urography:

Imaging technique for differential diagnosis of hydronephrosis, identification of a lower pole renal artery, and to identify associated kidney malformations.

Whitaker test:

Invasive measurement of the renal pelvis pressure during infusion through a percutaneous nephrostomy with 10 ml/min. The bladder pressure is subtracted from the renal pelvis pressure; the difference should be lower than 20 cm water column. Due to the invasiveness of the test, it is seldom used in practice.

Differential diagnosis of UPJ Obstruction

Please see section hydronephrosis. In children; Megacalycosis, megaureter, higher grade vesicoureteral reflux.

Treatment of UPJ Obstruction

Regular monitoring of renal function is sufficient in the absence of symptoms and even fractional renal function.

Indications for Surgery:

- Significant obstruction in renal scintigraphy

- Decreasing fractional renal function (&li;40%)

- Equivocal obstruction in renal scintigraphy with recurrent flank pain, pyelonephritis, or nephrolithiasis.

Conservative management with regular renal scintigraphy is indicated in the absence of symptoms and with good renal function on the affected side.

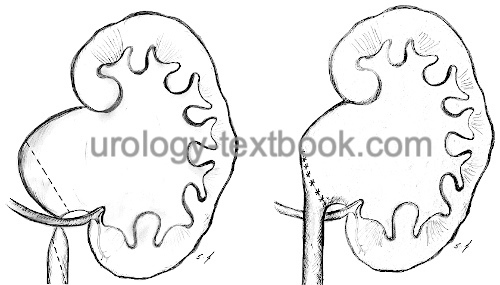

Pyeloplasty

The most popular pyeloplasty is the dismembered Anderson-Hynes technique, which can be done via an open lumbar, open subcostal, laparoscopic, retroperitoneoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach (Munver et al., 2004). The Anderson-Hynes technique consists of the transection and reduction of the renal pelvis, excision of the narrow ureteropelvic junction, spatulation of the proximal ureter, and reanastomosis of the proximal ureter to the renal pelvis (end-to-side). If a lower pole renal vessel is present, the ureter is repositioned after transection, and anastomosis is done anterior to the vessel. For surgical technique and complications, see sections open surgical technique of pyeloplasty and laparoscopic technique of pyeloplasty.

Antegrade or Retrograde Endopyelotomy:

After retrograde access (ureteroscopy) or antegrade access to the ureteropelvic junction, an endoscopic incision of the narrow segment (posterior position to avoid any lower pole vessel) is done with a cold knife, laser fiber or with special cutting devices. Endopyelotomy is an option if a lower pole renal vessel has been excluded and after failed pyeloplasty. Larger series have reported success rates around 75–90%. The endopyelotomy is seldom used in children.

Nephrectomy:

UPJ obstruction for UPJ-obstruction with a low fractional renal function (<10--20% of total renal function). Nephrectomy is usually possible with a minimally invasive technique (laparoscopic or retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy).

| Ureter Anatomy | Index | Duplex kidney |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Munver u.a. 2004 MUNVER, R. ; SOSA, R. E. ; PIZZO, J. J. del: Laparoscopic pyeloplasty: history, evolution, and future.In: J Endourol

18 (2004), Nr. 8, S. 748–55

Tan und Smith 2004 TAN, B. J. ; SMITH, A. D.: Ureteropelvic junction obstruction repair: when, how, what?

In: Curr Opin Urol

14 (2004), Nr. 2, S. 55–9

Deutsche Version: Harnleiterabgangsenge

Deutsche Version: Harnleiterabgangsenge