You are here: Urology Textbook > Penis > Urethral stricture

Urethral Stricture: Causes, Diagnosis and Treatment

Definitions

Urethral stricture is a fixed narrowing of the urethra with variable amounts of fibrotic tissue (Gozzi et al., 2008a) (Peterson et al., 2004). Anterior urethral stricture is the preferred term for the narrowing of the penile and bulbar urethra, which is surrounded by corpus spongiosum. Anterior urethral stricture is associated with spongiofibrosis (scarring of the corpus spongiosum) and is most often caused by infection and direct (iatrogenic) injury. Posterior urethral stenosis is the preferred term for narrowing of the membranous urethra, the prostatic urethra, or the bladder neck, which are not surrounded by corpus spongiosum and are not associated with spongiofibrosis. Narrowing of the membranous urethral after pelvic fracture should be termed pelvic fracture urethral (disruption) injury (Latini et al., 2014).

Epidemiology

Urethral stricture is more common in the elderly population. In developed countries, the prevalence is 600–900 per 100.000 males. The figures are much higher in developing countries where untreated infections are a relevant cause for urethral strictures.

Etiology (Causes) of Urethral Strictures

Trauma:

A pelvic fracture with distraction injury of the membranous urethra leads to a posterior urethral stenosis after defect healing. Direct perineal trauma leads to a compression injury of the bulbar urethra with development of bulbar urethral stricture (straddle injury). Even trivial perineal trauma without complications can cause urethral stricture after years; the trauma is often not remembered by the patient. Traumatic penile urethral strictures usually result from blunt injury or manipulation through the urethra.

Infections:

Gonorrhea used to have a high proportion in the genesis of anterior urethral strictures; timely antibiosis has made this complication rare. The causal relationship between infection and urethral stricture has not been established for other urethritis pathogens.

Iatrogenic:

After endoscopic surgery (TURP) or prolonged catheterization, pressure necrosis or direct injury usually occurs in the bulbar urethra. Risk factors for urethral stricture after catheterization are latex catheters, thick lumen catheters, ICU patients, and urinary tract infections. TURP with antibiotic prophylaxis and early catheter removal decreases the stricture rate.

Bladder neck stenosis:

Scarring narrowing of the bladder outlet is a typical complication after TURP.

| Do you want to see the illustration? Please support this website with a Steady membership. In return, you will get access to all images and eliminate the advertisements. Please note: some medical illustrations in urology can be disturbing, shocking, or disgusting for non-specialists. Click here for more information. |

Membranous urethral stenosis:

Membranous urethral stenosis may develop after radiotherapy or surgery for prostate carcinoma.

Lichen sclerosus:

Lichen sclerosus of the glans may leads to strictures of the navicular fossa. Subsequently, urethral stricture disease of the anterior urethra may result from urine extravasation into the periurethral glands.

Congenital:

Uncommon, if limited (by definition) to children before erect ambulation without a history of trauma or infection.

Pathology of Urethral Stricture

Depending on the extent of the fibrotic reaction, urethral strictures are classified into epithelial or spongiofibrotic lesions. Malignant causes for urethral stricture are rare; see section cancer of the male urethra.

Signs and Symptoms

- Obstructive (weak urine stream, residual urine, urinary retention) or irritative (pollakiuria, urgency, and nocturia) lower urinary tract symptoms.

- Urinary tract infections, prostatitis, epididymitis.

- Palpation can assess the fibrotic component of urethral stricture.

Diagnosis of Urethral Stricture

Uroflowmetry:

The uroflowmetry curve has a pathognomonic plateau shape and a long voiding time. The maximum flow is reached quickly and is typically below 10 ml/s.

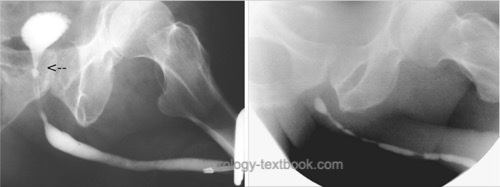

Retrograde urethrography:

Correctly determining the stricture length is essential for treatment decisions; images with a perpendicular beam path to the urethra are necessary. Especially for imaging of bulbar strictures, a clear oblique patient position during retrograde urethrography is needed.

|

|

Voiding cystourethrography:

VCUG is used for imaging of proximal strictures and may be combined with retrograde urethrography to judge stricture length.

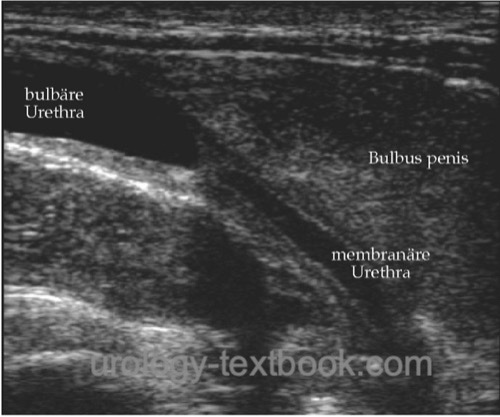

Ultrasound imaging:

Ultrasound imaging of urethral strictures is possible with a perineal or penile probe position after filling the urethra with lubricant gel. With experience, sonography is highly accurate in diagnosing stricture length and periurethral scarring.

|

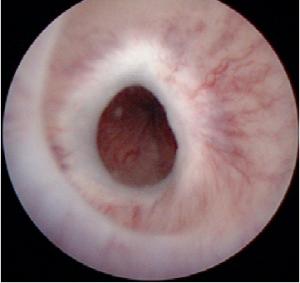

Cystoscopy:

Cystoscopy is used to inspect the stricture and to perform a biopsy if a malignant stricture is possible. Pediatric cystoscopes or ureterorenoscopes are helpful in patients with a narrow urethra.

|

Treatment of Urethral Stricture

Initial treatment for urinary retention:

Insert a thin transurethral indwelling catheter or suprapubic catheter. Transurethral dilatation should only be performed by experienced urologists (see below).

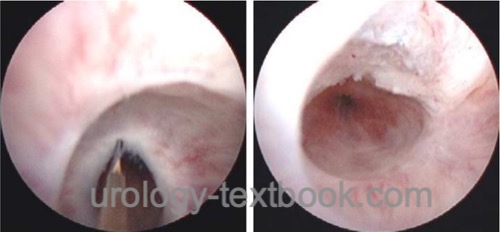

Direct Vision Internal Urethrotomy:

Direct vision internal urethrotomy (DVIU) is the treatment of the first choice for short urethral strictures without pronounced spongiofibrosis.

Surgical technique:

A transurethral incision of the stricture at 12 o'clock is done under direct endoscopic vision. The traditional internal urethrotomy (by Sachse) uses a cold knife. Alternatively, the stricture can be transected using a laser fiber (Nd:YAG, holmium, KTP). Blind internal urethrotomy (Otis) is used with palliative intent for long urethral strictures. See the section internal urethrotomy for details of DVIU and complications.

|

Results of Internal Urethrotomy:

Healing (no recurrence of the stricture) is possible between 20–70%. Recurrence may occur up to 3 years after surgery. The risk of recurrent stricture can be reduced by self-calibration/dilatations performed at intervals after urethrotomy (by the patient). Applying a cortisone ointment (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide) together with self-dilatations reduces the recurrence rate by an additional 10% (Verla et al., 2023). A second session after recurrent stricture does little to increase the cure rate. The best results are seen for short bulbar strictures without marked spongiofibrosis (healing up to 74%) and the worst in long penile strictures with recurrence rates above 80%.

Balloon dilatation of the urethra:

Special urethral catheters with long balloon sections are used, inflated under fluoroscopic guidance with high pressure to 24 CH outer diameter for several minutes. The procedure can be performed without anesthesia. The goal is to dilate the stricture without the renewed stimulus of scarring. Balloon urethral dilatation can cure epithelial strictures; strictures with marked spongiofibrosis will recur, comparable to the results of urethrotomy (Liao et al., 2020).

Using a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter for urethral dilatation can reduce the frequency of or time to recurrent stricture (Elliott et al., 2022). In patients with a recurrent stricture in the bulbar urethra, a randomized study showed, after six months, a recurrence rate of 25% vs. 73% (Optilume balloon catheter versus conventional endoscopic therapy).

Bladder neck incision:

A bladder neck incision is the first treatment option for bladder neck stenosis. The stenosis is incised at the 12, 4, and 8 o'clock position, with a cold knife, a monopolar hook, or a laser.

Anastomotic urethroplasty:

Anastomotic urethroplasty is a definitive treatment option for short urethral strictures (<2cm) with significant spongiofibrosis when initial urethrotomy recurs.

Surgical technique:

Identification and complete excision of spongiofibrosis after mobilization of the urethra, spatulation of the urethra and tension-free end-to-end anastomosis. The closer the stricture is to the membranous urethra, the longer the stricture may be for successful anastomosis (up to 5 cm have been reported). The non-transecting anastomotic bulbar urethroplasty (NTABU) is treatment option for short bulbar urethral strictures without pronounced spongiofibrosis with fewer complications. See section Anastomotic urethroplasty for details of surgical technique and complications.

Results:

Cure rates: 80–95%. Factors for a successful surgery are a short stricture, primary repair, and bulbar location. Major complications include recurrence of stricture, fistula formation, penile shortening, penile deviation, and erectile dysfunction.

Meatoplasty for meatal stricture:

After the longitudinal incision of the stricture, the defect is covered with pedicled penile skin flap. Alternatively, the urethral defect is covered with an oral mucosa graft. The second layer of neo-urethral closure is achieved by skin closure. In cases of exclusively distal meatus stenosis without involvement of the navicular fossa, longitudinal incisions and transverse sutures ventrally and dorsally are sufficient.

Results:

For patients with balanitis xerotica obliterans, recurrences are more frequent with skin flap repair; better results are reported with oral mucosa grafting.

Single-stage urethroplasty:

After incision or excision of the urethral stricture, the urethral defect is closed with the help of a tissue transfer (graft of flap). Grafts are used after longitudinal incision of the urethral stricture; the strictured urethra is left in place. The urethral defect is closed by tissue transfer; the graft can be placed dorsally, laterally or ventrally. Oral mucosa grafts are most common for free tissue transfer. If a complete excision of the strictured urethra is necessary, a tubularized tissue transfer must be constructed (pedicled skin flaps or free grafts). See the section on single-stage urethroplasty for details of the surgical techniques.

Results:

Good results with 75–90% long-term cure rates are reported for short onlay urethroplasty. Long-segment urethroplasty, especially with tubular reconstruction, has a higher complication rate. Significant complications include re-stricture, fistula formation, urethral diverticulum, and impotence.

Two-stage urethroplasty:

First stage (marsupilization of the urethra): longitudinal urethral incision and complete resection of urethral scar tissue; the urethral defect is covered with a split-thickness skin graft or oral mucosa. The urethral defect is left open for several months to allow healing; the patient voids via the perineal urethral opening.

Second stage: incision of the graft-skin border and careful dissection of the graft edges with preservation of the neovasculature; the graft (neourethra) is closed longitudinally over a transurethral catheter. Cover the neourethra with subcutaneous tissue (dartos flap). See the section two-stage urethroplasty for details.

Results:

A long-term cure of 80% is reported for patients with complex stricture disease or after failed hypospadias repair with long urethral defects. Recurrent stricture is possible even after ten years of surgery. Further complications include fistula, penile shortening, penile deviation, and erectile dysfunction.

Y-V plasty:

The Y-V plasty is indicated for recurrent bladder neck stenosis after transurethral incision(s). Y-V plasty can be done with a retropubic or laparoscopic (robotic-assisted) approach. The anterior bladder neck and prostatic urethra are incised, and the incision is continued into the anterior bladder wall like a Y. The defect is sutured, forming a V, which places healthy bladder tissue into the bladder neck scar.

Transurethral Stent Placement After Internal Urethrotomy:

Partially good results were reported in small series with permanent (UroLume) or removable (Memokath) urethral stent implantation. Long-term results for UroLume were disappointing, with a cure rate of under 30% (Shah et al., 2003b). Permanent urethral stents may cause perineal pain, stent migration, and difficult-to-treat recurrent strictures. The structure of Urolume is incorporated into the urethra, making removal difficult. The removable expandable metallic urethral Memokath stent prevents early recurrent stricture after urethrotomia with favorable side effects (Jordan et al., 2013), but more extensive trials are unavailable.

| Corpus cavernosus thrombosis | Index | Lichen sclerosus |

Index: 1–9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

References

Barbagli u.a. 2003 BARBAGLI, G. ; PALMINTERI,

E. ; LAZZERI, M. ; GUAZZONI, G.:

Anterior urethral strictures.

In: BJU Int

92 (2003), Nr. 5, S. 497–505

S. Bugeja, D. E. Andrich, and A. R. Mundy, “Non-transecting bulbar urethroplasty.,” Translational andrology and urology, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 41–50, 2015.

S. P. Elliott et al., “One-Year Results for the ROBUST III Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Optilume Drug-Coated Balloon for Anterior Urethral Strictures.,” J Urol, vol. 207, pp. 866–875, Apr. 2022, doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002346.

Gozzi, C.; Tritschler, S.; Bastian, P. J. & Stief, C. G.

[Management

of urethral strictures].

Urologe A, 2008, 47,

1615-1622

G. H. Jordan et al., “Effect of a temporary thermo-expandable stent on urethral patency after dilatation or internal urethrotomy for recurrent bulbar urethral stricture: results from a 1-year randomized trial.,” J Urol, vol. 190, no. 1, pp. 130–136, 2013.

J. M. Latini, J. W. McAninch, S. B. Brandes, J. Y. Chung, and D. Rosenstein, “SIU/ICUD Consultation On Urethral Strictures: Epidemiology, etiology, anatomy, and nomenclature of urethral stenoses, strictures, and pelvic fracture urethral disruption injuries.,” Urology, vol. 83, no. 3 Suppl, pp. S1–S7, 2014.

R. S. Liao, E. Stern, J. E. Wright, and A. J. Cohen, “Contemporary Management of Bulbar Urethral Strictures.,” Reviews in urology, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 139–151, 2020.

N. Lumen, F. C. Juanatey, K. Dimitropoulos, and F. E. Martins, “EAU Guidelines: Urethral Strictures,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urethral-strictures.

Peterson und Webster 2004 PETERSON, A. C. ;

WEBSTER, G. D.:

Management of urethral stricture disease: developing options for

surgical intervention.

In: BJU Int

94 (2004), Nr. 7, S. 971–6

F. Schreiter and G. H. Jordan, Eds., Reconstructive Urethral Surgery. Springer Medizin Verlag Heidelberg, 2006.

D. K. Shah, E. M. Paul, and G. H. Badlani, “11-year outcome analysis of endourethral prosthesis for the treatment of recurrent bulbar urethral stricture.,” J Urol, vol. 170, no. 4 Pt 1, pp. 1255–1258, 2003.

W. Verla et al., “Is a Course of Intermittent Self-dilatation with Topical Corticosteroids Superior at Stabilising Urethral Stricture Disease in Men and Improving Functional Outcomes over a Course of Intermittent Self-dilatation Alone? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.,” European urology open science, vol. 51, pp. 95–105, May 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.euros.2023.01.011.

H. Wessells, A. Morey, A. Vanni, L. Rahimi, and L. Souter, “AUA Guideline: Urethral Stricture Disease.” [Online]. Available: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/urethral-stricture-guideline

Deutsche Version: Ursachen, Diagnose und Therapie der Harnröhrenstriktur

Deutsche Version: Ursachen, Diagnose und Therapie der Harnröhrenstriktur